By David South, Development Challenges, South-South Solutions

We all know that green is good, but often the best way to encourage recycling and other environment-improving activities is to put in place economic incentives. It is one thing to admonish people and tell them something is the right thing to do; it is another to make keeping a clean environment pay.

Many initiatives across the global South have proven it is possible to develop an economy of recycling and garbage collection in poor neighbourhoods. These economies take many forms and models.

At the most basic end of the scale are the desperate, survival-driven examples of recycling. In countries likeIndia, recycling can be purely a question of survival – people are so poor they can’t allow anything that might have income potential go to waste. Other countries are very familiar with large numbers of desperately poor people picking through garbage dumps and waste to eke out a living. Or, for example in Brazil, as in many other countries, it’s common to see poor and homeless people picking through garbage on the streets.

These are examples of degrading ‘green’ economies. But there other ways to encourage waste recycling that offer real income benefits and life improvements.

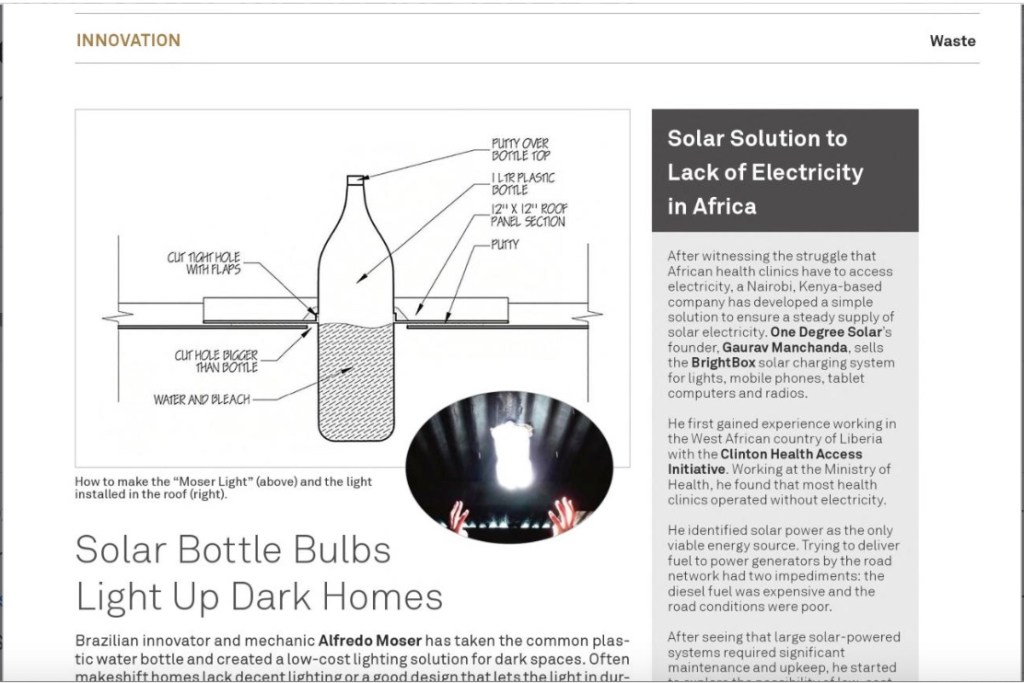

Brazil, a world leader in waste recycling and green technologies, has pioneered the recycling of plastic bottles, aluminum, steel cans, solid plastic waste and glass. And now energy companies inBrazilhave created credit schemes that encourage waste recycling while giving people real economic benefits in return for doing the right thing for the environment. The first scheme went so well, it quickly inspired others to replicate its programme in other poor communities.

Coelce (http://www.coelce.com.br/default.aspx) is a power company in the Ceará State in northeastern Brazil. The company is primarily engaged in the distribution of electrical power for industrial, rural, commercial and residential consumption. In 2007 it set up Ecoelce (http://www.coelce.com.br/coelcesociedade/programas-e-projetos/ecoelce.aspx), a programme allowing people to recycle waste in return for credits towards their electricity bills. The success of the programme led to an award from the United Nations.

The programme works like this: people bring the waste to a central collection place, a blue and red building with clear and bright branding to make it easy to find. In turn they receive credits on a blue electronic card – looking like a credit card – carrying a picture of a child and arrows in the familiar international recycling circle.

These credits are then used to calculate the amount of discount they should receive on their energy bill. The scheme is flexible, and people can also use the credits for food or to pay rent. In 2008, after its first year, the scheme had expanded to 59 communities collecting 4,522 tons of recyclable waste and earning 622,000 reais (US $349,438) in credits for 102,000 people. People were receiving an average of 5 to 6 reais (US $2.80 to US $3.37) every month towards their energy bills. A clear success leading to an expansion of the scheme.

Now in Ceará’s state capital, Fortaleza (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fortaleza), – population 3.5 million – there are more than 300,000 people recycling a wide range of materials, from paper, glass, plastics, and metals to cooking oil to get electricity discounts, according to the Financial Times.

In Brazil’s second largest city, Rio de Janeiro, a favela clean-up programme is being run by electricity firm Light S.A. (http://www.light.com.br/web/tehome.asp), which took its inspiration from the success of the Ecoelce experience.

The number of favelas, or informal slum neighbourhoods (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Favela), in Rio is debated: according to the federal government, there are 1,020 favelas, while Rio’s housing department lists 582. The government has been trying to tackle the law and order problems in these neighbourhoods – many are plagued with violent drug gangs – and endemic poverty. It calls this programme “pacification” (http://brazilportal.wordpress.com/2011/10/20/rios-top-cop-talks-public-safety-policy-favela-pacification-program/) as it tries to bring law and order and boost economic development and social gains.

Recycling programmes are helping to bring improvements to life in the favelas by simultaneously cleaning up neighbourhoods and boosting household wealth.

Light S.A. is a Brazilian energy company working in the generation, transmission, distribution and marketing of electricity. It distributes to 31 municipalities inRio de Janeiroand has around 3.8 million customers.

According to the Financial Times, the Light project pays residents 0.10 reais per kilogram of paper and plastic (US .5 cents). It also pays 2.50 reais per kilogram of aluminum and lead (US $ 1.40).

Importantly for community relations, the scheme is open not just to favela residents but to nearby middle class neighbourhoods.

“The idea is to unite the community and the people living around it,” Fernanda Mayrink, Light’s community outreach officer, told the Financial Times.

The project has helped improve theSanta Martafavela ofRio, where police have been working since 2008 to take back the neighbourhood from the control of violent drug gangs. Community police officers can now do their job of taking care of safety for the 6,000 residents.

“You don’t see drugs and guns any more but you do see lots of rubbish,” Mayrink said.

“This project encourages recycling within the company’s concession area and at the same time contributes to sustainable development and the consumer’s pocket. Light wins, the customer wins (and) the environment wins.”

In Vietnam, the NGO Anh Duong (http://www.anhduonghg.org/en/) or “Sun Ray” shows schoolchildren how to collect plastic waste to sell for recycling. In return, their schools receive improvements and the students can win scholarships. It is estimated ruralVietnam is littered with 100 million tons of waste every year. Much of it is not picked up.

The project is operating in 17 communities in Long My and Phung Hiep districts in southernVietnam, mobilising children from primary and secondary schools. School children wearing their uniforms fan out in groups and collect the plastic waste. The money made from selling the plastic waste is being used to improve school facilities and fund scholarships for poor children.

In 2010, the project reported that 10,484 kilograms of plastic waste was collected by 26,015 pupils. This provided for 16 scholarships for school children.

The Anh Duong NGO was set up by a group of social workers with the goal of community development. They target the poorest, bringing together the entire community and seek out “low cost and sustainable actions”. The NGO has a mix of specialties, from agriculture to aquaculture, health, microfinance and social work.

Published: November 2011

Resources

1) A travelling exhibit, In The Bag: The Art and Politics of the Reusable Bag Movement, showcases bags and art produced by communities throughout the world and by individual artists. Website:http://www.unrisd.org/80256B3C005BE6B5/%28httpNews%29/D1AB353A91EC2466C125793600519C7B?OpenDocument

2) EPAP guide: Based on extensive research throughout Mongolia by UNDP, this guide includes the application of the Blue Bag project to Mongolia’s sprawling slum districts surrounding the capital Ulaanbaatar. Website:http://tinyurl.com/yfkn2dp

Development Challenges, South-South Solutions was launched as an e-newsletter in 2006 by UNDP’s South-South Cooperation Unit (now the United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation) based in New York, USA. It led on profiling the rise of the global South as an economic powerhouse and was one of the first regular publications to champion the global South’s innovators, entrepreneurs, and pioneers. It tracked the key trends that are now so profoundly reshaping how development is seen and done. This includes the rapid take-up of mobile phones and information technology in the global South (as profiled in the first issue of magazine Southern Innovator), the move to becoming a majority urban world, a growing global innovator culture, and the plethora of solutions being developed in the global South to tackle its problems and improve living conditions and boost human development. The success of the e-newsletter led to the launch of the magazine Southern Innovator.

Follow @SouthSouth1

Google Books: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=waeXBgAAQBAJ&dq=Development+Challenges+February+2008&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Slideshare: http://www.slideshare.net/DavidSouth1/development-challengessouthsouthsolutionsfebruary2008issue

Southern Innovator Issue 1: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Q1O54YSE2BgC&dq=southern+innovator&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Southern Innovator Issue 2: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Ty0N969dcssC&dq=southern+innovator&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Southern Innovator Issue 3: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=AQNt4YmhZagC&dq=southern+innovator&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Southern Innovator Issue 4: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=9T_n2tA7l4EC&dq=southern+innovator&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Southern Innovator Issue 5: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=6ILdAgAAQBAJ&dq=southern+innovator&source=gbs_navlinks_s

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5311-1052.

© David South Consulting 2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.