Researcher and Writer: David South

Consultancy: David South Consulting

Publisher and Client: USAID

Published: 2000

Results Review and FY 2002 Resources Request (USAID/Mongolia March 17, 2000): “Improving Productivity and Exports: A key to Mongolia’s growth is increasing non-traditional exports. However, with less than ten years of free-market experience, Mongolia has little experience on how to accomplish this objective. In response, USAID began a six-month program in January2000 to: 1) instruct Mongolians on the principles of competitive analysis; 2) establish benchmark data that will help Mongolians to rank their country against others vis-a-vis key competitiveness indicators; 3) create Mongolian-specific case studies to illustrate successful competitive behavior or pinpoint obstacles and constraints; 4) work with business leaders from garment, cashmere, meat, information technology and tourism industries to apply competitiveness tools and focus attention on key priorities for government and private sector action. Over six hundred influential Mongolians from government, private sector and academia are participating in the process. USAID hopes to assist in developing a national action plan for competitiveness in the fall, once a new government is in place.

The Global Bureau’s Global Technology Network (GTN) which develops business linkages between U.S. and Mongolian firms has been active for two years. GTN efforts have fallen short of expectations with only three relatively modest linkages established in 1999. In January 2000, through its relationship with the International Executive Service Corps (IESC), GTN sponsored Mongol Construct 2000, a trade mission to the United States for construction firms. The purpose of the mission was to learn about advanced construction techniques and develop linkages with U.S. firms. In 2000 IESC will expand its assistance to a select group of garment manufacturers, who are attempting to establish non-traditional markets.“

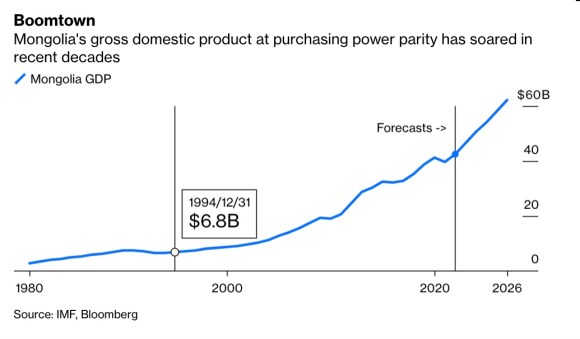

Background: This excerpted text is from a business prospectus prepared in 1999 for USAID to promote construction opportunities in Mongolia to the US construction industry. At the time, Mongolia was in the grip of a severe crisis, called one of “the biggest peacetime economic collapses ever”. By 2012, Mongolia was called the “fastest growing economy in the world”. It is proof the foundations for Mongolia’s recovery from crisis were laid in the late 1990s.

“No other Asian country enjoys more political freedom today than Mongolia. And no other Asian country has shown greater commitment to open markets. But Mongolia has received little reward for its efforts.” Fortune Magazine, December 1998

Discover a New Democracy

Mongolians are some of the highest per capita donor recipients in the world: On average US $50 per person. The vast majority of this aid is targeted at infrastructure projects. Mongolia in 2000 is an opportunity waiting for American business. Democratic, with a free market economy, the country offers regulatory freedom, a belief in the private sector setting standards and a pro-Western attitude friendly to American companies.

Mongolia’s history is marked by the rise and fall of cities, the ebb and flow of political and economic systems. The country has experienced being the largest empire for its time in the 13th century, to being occupied by foreign powers. Economically and socially the country has lived through feudalism, communism and now, capitalism. The one thing that has remained stable throughout this rich history has been the nomadic way of life. Livestock remains to this day a major pillar of the economy and contributes to one of the country’s major foreign currency earners, cashmere wool.

After over 70 years of communist rule, Mongolians finally turned their backs on communism and robustly embraced free markets and democracy in 1996 with the election of the Democratic Coalition. A gradual opening up of the country had begun under the ruling Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party after the collapse of the Soviet Union and under pressure from peaceful public demonstrations.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the country suffered what many economists have called the largest peacetime economic collapse in the 20th century.

While it is a fact that Mongolia’s economy is severely underdeveloped, both in terms of infrastructure and diversity, it is also true the country is the freest in Asia. As Fortune Magazine noted in a December, 1998 issue, “No other Asian country enjoys more political freedom today than Mongolia. And no other Asian country has shown greater commitment to open markets. But Mongolia has received little reward for its efforts.” Mongolia, for American business, offers a win-win situation, an opportunity to join in the building of a strong democracy in Asia while tapping the rich resources, both natural and in human capital. American businesses can enjoy a regulatory environment that is more flexible than in the United States, and a government that lets businesses do what they do best: serve the needs of customers and make money.

Youthful

A Bright Young Future

Demographically, Mongolia is a very young country. A by-product of high birth rate policies during the communist period, 60 per cent of Mongolia’s population are aged between 1 and 24, with 37.6 per cent between the locally accepted definition of youth of 15 to 34. In 1998 the New York Times Magazine called Mongolia “The youngest place on earth”. Even a cursory glance at the streets of the capital, Ulaanbaatar (population 600,000), will reveal a young population taking their fashion and cultural cues from the West, and who hold correspondingly Western aspirations to own homes and start businesses. Mongolia enjoys exceptionally high rates of literacy ( 96 per cent), post-secondary enrolment (65,089 students in 1998) and the urban population quickly embraced Western consumer products as they became available.

Growing

The Construction and Environmental Services Industry in Mongolia

Today, Mongolia officially has 100 architectural and engineering design companies and over 500 construction companies. Of these, 40 are considered large operations with their own in-house design and engineering outfits, or who have a close relationship with one or more companies that either manufacture or import construction materials. The country is a rich resource for raw materials for the construction industry, but this vast wealth remains under-utilised. According to geological surveys spanning the decades from 1930 to the 1990s, over 200 deposits were discovered that could be tapped for construction materials.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, there were few permanent standing structures in Mongolia, apart from Buddhist monasteries and royal palaces. At the beginning of the 20th Century most Mongolians lived in the round ger felt tent. It wasn’t until the communist revolution that construction of sedentary dwellings and buildings in the country picked up pace. In 1924, three years after the 1921 revolution, the State Committee for Construction was established (by 1926 it became the Construction Department of the Ministry of Industry), and undertook the large-scale construction of buildings based on European designs.

From the 1960s the construction industry in Mongolia emerged as the country industrialised. Mongolia received aid from both China and Russia up to the Sino-Soviet dispute, and both countries were the main funders for construction projects. Many buildings in the downtown of the capital were built by the Chinese government.

Up until the election of the Democratic Coalition in 1996, all construction activities were conducted under the direction of the state. Building booms took place in the 1970s and 1980s as the communist government tried to meet the demand for apartments and other facilities. At its peak in 1989, the construction sector made up 10 per cent of the gross national product. With the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the 1980s, many building projects in Mongolia ground to a halt as Soviet subsidies were withdrawn. Across the country it is possible to see the empty shells of apartment buildings, holiday resorts and half-built sports stadiums.

The Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party, under popular pressure for a change, began to gradually make the shift to free markets and democracy. The first state privatization programme began in 1993 under the direction of international experts. It wasn’t until the election of the Democratic Coalition in 1996 that significant reforms were taken to fully introduce a free market economy. And it wasn’t until 1997 and 1998 that the fruits of these measures started to appear.

The construction industry was fully privatised in 1998, with companies becoming limited or wholly owned entities. There now exists a mix of private and public companies in this sector. All of the companies are in the early stages of learning how to work and prosper in the free market.

The legacy of working under a command economy has left many companies ill-equipped and under-funded, many not operating at full capacity or not at all.

The private sector has shown itself to be capable of initiating real estate development projects, most commonly the building of private apartments, shopping complexes and small hotels.

Weaknesses in management and financing do lead to long delays, poor quality and in some cases, the abandonment of a construction project mid-way. According to the State Statistical Office, the construction sector shrank from 1991 to 1994. In 1994, activity increased 26 per cent from 1993. Since then the gross national product has averaged growth of 3.3 per cent, but still has not caught up with the rate at the end of the 1980s.

The environmental services sector has received a significant boost from international donors working in Mongolia. Various donor funded projects are building and renovating facilities using energy-efficient technology. These donors have also conducted training workshops and education campaigns for local construction companies. Being a very cold country, awareness is high over the financial and environmental benefits of energy-efficient techniques. Construction techniques, however, are weak and Mongolia has a long way to go in utilizing these technologies efficiently.

It is a misnomer to think most Mongolians are wandering nomads. In fact the majority of the population of 2.4 million now live a sedentary lifestyle in small towns or in the big cities of Ulaanbaatar, Erdenet and Darkhan. Under communism these urban centres were economically dependent on state enterprises, many of which now have either gone bankrupt, idle or have been privatized. There is currently a significant migration to the capital from these economically devastated communities. Officially the government was able to track 6,518 people, mostly between the ages of 18 and 39, moving to the capital in the first half of 1998 – a 60 per cent increase on 1997. Unofficial migration to the capital is believed to be far higher.

At present a majority of the population still live in ger tents or sub-standard makeshift wooden housing. The construction industry cannot meet the high demand for modern housing, with amenities like running water, toilets and electricity.

“The business atmosphere in Mongolia is inviting and [our] partnership has faced very few obstacles while entering the market. Based on our positive experience here, we plan to continue and expand our presence in the Mongolian marketplace.” Mrs. Bolormaa Reiner, Representative Johnson and Johnson-Mongolia

Foreign Aid

Economic Prospects for the Country

Large donor community

Along with the collapse of the Soviet Union, Mongolia also lost significant economic subsidies, which contributed to the severe crisis of the early 1990s. The World Bank has estimated these subsidies reached a third of Mongolia’s GDP in the late 1980s. Since then international donors have played a key role in helping to restructure the Mongolian economy to adapt to the demands of a market economy.

Infrastructure has always been a weak point for Mongolia, and it was considered the most isolated and underdeveloped of the former Soviet bloc countries. International donors have placed infrastructure development at the top of their agendas. Since 1997 foreign aid in the form of grants and loans has hovered around US $250 million, with the vast majority of this aid going towards infrastructure development. Priority areas are highways and transportation, power stations and communications. By sector the aid breaks down as follows: 30 per cent to mining, 27 per cent to energy, 19 per cent to transport, eight per cent to communications, five per cent to social security and three per cent to other areas. The donor community and the Mongolian government want to dig the country out of decades of underdevelopment, which currently hampers the budding private sector from becoming more sophisticated.

These large-scale infrastructure projects offer enormous opportunities for US firms experienced in working in cold-weather conditions. There are also opportunities to develop world class office space for these international donors, something that is currently lacking in Ulaanbaatar.

Foreign investment to date

Actual large-scale foreign investment to the country has been slow coming and still doesn’t represent a major economic opportunity. The major players in direct foreign investment outside of development aid have been Mongolia’s old neighbours, Russia (20 per cent) and China (33 per cent). This decade the country has attracted US $200 million in foreign investment and registered 840 jointly owned or wholly owned ventures.

New-found affluence

It is estimated that around five per cent of the capital’s population fit into a middle or upper income category. The late 1990s have seen the emergence of a new breed of affluent Mongolians. Many of these affluent Mongolians struck it rich trading in once-unobtainable consumer products or servicing the expanding foreign community. This class of traders have developed a sophisticated taste for all things Western – Mercedes Benz cars, four-by-four jeeps and western fashions. Vehicle registrations have steadily risen since the introduction of a market economy. In 1996 the number of vehicles was 65,020; by 1997 it was 70,088.

New home owners

In 1998 50,000 families became homeowners as a result of privatization of apartments. All the apartments are of Soviet era and do not meet the aspirations of the growing middle class. Many of these new homeowners immediately set about renovating these apartments, installing modern appliances and furniture. A significant minority is renovating apartments with the intention of selling them on to wealthier Mongolians or foreigners. The high number of renovations and additions to buildings in the capital is also indicative of other things: the economy has changed and existing buildings do not meet the new demands, and that people have money to pay for the renovations.

Business Opportunities

USAID has identified the following opportunities in the Mongolian construction sector:

– Donor-funded projects: Large-scale infrastructure projects that are funded by loans or grants from international donors, are a safe bet. These projects require management and technical expertise that is often difficult to find locally. This includes projects that require an international tender.

– Fully funded foreign projects: Any project requiring a building that meets international standards. International companies have little choice when it comes to finding adequate office or retail space.

– Low-cost labor: The Mongolian workforce is highly literate and often speak a second language, usually Russian amongst older workers, and English amongst the young. Unemployment levels are high in Mongolia and workers are keen to get a job. Generally salaries are as follows:

– Manager: US $250

– Accountant: US $200

– Engineer: US $150

– Secretary: US 100

– Driver: US $100

– Qualified worker: US $100

Source: FIFTA

– Donors: Many large-scale projects are directly funded by donor grants or loans and therefore are a low-risk, reliable source of income. At the June, 1999 donors meeting in Ulaanbaatar, US $320 million was pledged, the largest amount in eight years of donor funding. Most of these pledges are targeted at “hard” infrastructure and private sector development.

– Imports rule: Imported construction materials dominate the marketplace and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Many of the materials are poor quality and from China. American companies can attract customers with their obvious advantages in both quality and innovation.

– Large resource base: Mongolia’s large wealth of mineral resources is inefficiently utilized, with many mines and factories working under capacity or not at all. These resources could be tapped to produce construction materials locally for the domestic market, or more lucratively, for the booming Chinese market hungry for resources.

– Very cold country: Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbaatar, is the coldest capital in the world. Mongolia’s winters dip below minus 40 Celsius, and for those who live in apartment buildings, this can be a difficult time. Many apartments are inadequately insulated, and dip below zero when the central heating system is disrupted due to poor maintenance. There is an urgent need for high-quality aluminium and plastic windows and doors. Budgets are tight in Mongolia yet many organizations spend vast sums to heat buildings. It has been proven that during the course of the winter heating costs can be reduced from Tg 4,200 (US $4.20) per square metre, to Tg 280 (US $0.28) in an energy efficient dwelling.

– Windows are expensive: Mongolia must import all windows and glass products. When the cost of freight is added, windows become an unnecessarily expensive portion of any construction bill. This is a business opportunity for any company who can domestically produce glass products and windows at a cheaper price than imports. A National Code for Insulation of Buildings is being revised and none of the existing windows and doors meet this requirement.

– No chemical industry: While Mongolia exports oil to China for refining, the country does not have a domestic chemical industry, and consequently plastic and rubber is imported for construction purposes. Stone tiles like marble are currently also imported from outside, despite this resource being available in Mongolia.

– Central heating and water unreliable: For those who live in apartment buildings, the regular disruptions to both the water and heating supply are not only inconvenient, but also bad for business. Technology that can by-pass relying on the central system (common to many Soviet-era cities, this system is wasteful and subject to regular breakdowns), is urgently needed. Alternative energy sources like solar power and wind can bring electricity to those who are not on the grid.

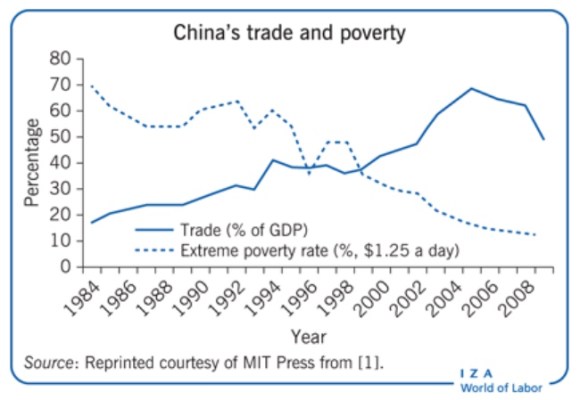

– Free trade zones: The towns of Sukhbaatar (Russian border) and Zamyn-Uud (Chinese border), both served by rail, are the focus of Mongolian government attempts at increasing cross-border trade. At Zamyn-Uud Japan has upgraded the customs house facilities and trans-shipment facility. On the Chinese side, a major trading market has been constructed and a boom is taking place based on trade with Mongolia.

“Arthur Andersen has had representation in Mongolia since 1993. We have been very active in the development of the accounting and auditing profession in Mongolia. January 1999, Arthur Andersen opened Arthur Andersen Mongolia Audit LLC.” Mr. C. L. Ruddell, Representative Arthur Andersen-Mongolia

What Do Mongolians Say They Need?

In interviews conducted by USAID, Mongolian government officials and construction companies detailed what they felt were the most urgent priorities:

– Education and training: The vast majority of engineers and managers in the Mongolian construction industry received their training under communism. They were trained to work under a centrally planned economy, and will need to learn how to thrive in a free market situation where there are no guarantees. The Construction Training Institute currently only offers courses to managers and engineers. Its curricula is out-of-date and awareness of modern construction techniques and standards is weak. Exposure to computer-assisted construction methods is urgently required as well as training in foreign languages.

– Awareness of International Standards: No Mongolian companies can offer state-of-the-art consulting on construction projects.

– Licensure, apprenticeships and guilds: Standards are very weak in the construction sector and there is not a highly developed mechanism to ensure construction managers, engineers and workers meet a minimum qualification.

– Being Earthquake-proof: While the National Design Codes and Regulations do stipulate that buildings must meet minimum requirements against earthquakes (Mongolia is located in a seismically active region, and severe earthquakes have happened), most buildings post-1989 fail to meet these requirements.

– Weak infrastructure: Developing the transportation infrastructure of Mongolia will be key to future improvements in the economy. The rapidly developing Chinese economy offers many opportunities to Mongolia if roads and highways can be upgraded.

– Better coordination and promotion: Working with FIFTA or the Foreign Investment and Foreign Trade Agency, Mongolian companies seeking foreign investment for projects need to improve their networking and presentation skills.

Obstacles and Market Risks

Corruption: While Mongolians will tell you corruption has reached all levels of government, it is important to keep in mind it does not come close to the levels of corruption found in other former Communist countries. Foreign businesses do not suffer from harassment or intimidation by criminal gangs.

Inexperience with the free market: Foreign businesses and travellers to Mongolia do experience difficulties communicating Western business concepts like consumer rights and service. It has to be said that over the past three years this has changed considerably for the better, and continues to improve as Mongolian businesses learn the importance of the axiom “the customer is always right”.

Differences between Mongolian and US standards: While Mongolia’s regulations and laws are different from those in the US, it is important to keep in mind that the regulatory environment in Mongolia can be much freer in some areas. Also, many of the new laws have been drafted based on US laws and Mongolia’s constitution was written upon the advice of US legal experts.

Harsh climate: The long cold winters do present problems for some foreign businesses not used to working in cold-weather climates. This is also an area where American companies are at a specific advantage.

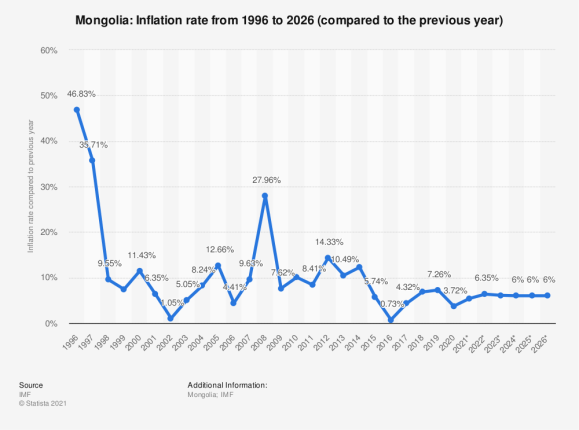

Financial instability: Mongolia has had a number of serious banking crises since the early 1990s. Many private and public banks are insolvent due to bad loans. This can lead to long delays to construction projects and/or non-payment of salaries.

Contract bidding: Only those contracts that are directly commissioned by the government will be subject to an open bidding. Private sector work is usually not subject to open bidding or design competitions.

Downtime: Since Mongolia does no international corporate presence in the capital, any technical problems to equipment or software can involve downtime and delays as parts or repairs are sought in China. It is important to take this into consideration when establishing an operation in Mongolia.

Advantages of Working in Mongolia

– Regulatory freedom

– Private-sector driven

– Market economy taking off

– Democratic

Privatization of Land: Can I Own Land in Mongolia?

The dual legacies of communism and nomadism have made the issue of private ownership of land in Mongolia a thorny one. The government has passed the necessary legislation to make owning land in urban areas possible. However, inexperience with the concept of owning property and the laws that govern this make buying land risky. It is advisable to get a reliable local partner and to use the services of a law firm that knows the Mongolian situation. Long-term leases are available and might be a good option.

Mongolian Government

Financial commitment to date:

The Ministry of Infrastructure Development has developed projects to encourage the production of construction materials locally. Due to financial constraints these projects have not been implemented. They include projects on cement, glass and paint production, rock processing, lime extraction and road development.

Government plans:

At this time the Mongolian government has not been able to develop a long-term strategy for the development of the construction sector. There are no specific policy incentives directly supporting real estate and housing development. The Ministry of Infrastructure is looking to the private sector to offer direction and guidance.

Future Opportunities

The Tumen River Project: The eastern portion of Mongolia is included in a major trade zone development project initiated by the United Nations Development Programme. The Tumen River Area Development Programme (TRADP) is focusing foreign investment and infrastructure upgrading on eastern Mongolian, North-East China, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and eastern Russia. This region has cumulatively attracted US $961 million from 1991 to 1997, with Mongolia’s second biggest trading partner, China, making significant development gains. While the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea has been a thorn in the Project’s side, both Mongolia and China are keen to push ahead with improving infrastructure and trade links. It is impossible to ignore the fact that China has made significant gains and that trade links with Mongolia continue to tighten.

A feasibility study is currently underway on a railway link from Arxan, China to Choibalsan, Mongolia, and possibly on to Ulaanbaatar. As donors begin to fund these projects it would be prudent for American businesses to start building a relationship in the region to take advantage of future contracts.

Commercial Street 2005: The City of Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia’s capital and commercial centre, has drafted the blue prints for the construction of a modern commercial and business centre for the next millennium. Commercial Street 2005 will offer infrastructure and services that match global standards. The current Soviet-era infrastructure of Ulaanbaatar is an impediment to future growth and is unsuitable for Mongolia’s new market economy.

The project covers 20 hectares of 1 km length in a historically vibrant part of the city. The city will pay for the engineering and infrastructure works for the complex and local businesses will pay for the construction of secondary buildings. Commercial Street 2005 is looking for foreign investment to participate in the building of a food supermarket, trade and service complex, a twin-towered international trade and service complex, a banking centre, a business centre and renovations to nearby apartment buildings. It is estimated the project will create 10,000 jobs and would cost an estimated US $100 million.

Darkhan: With a population around 55,000, Darkhan is as-yet an untapped opportunity. Located north of Ulaanbaatar and close to the border with Russia, Darkhan is linked by a good road and rail. Along with the mining town of Erdenet, Darkhan has a modern infrastructure. Having been trained to work in the former state industries that once dominated the city, the population is well-educated and skilled. Today, coal mining and agriculture are key to the economy. The city is potentially a good stable base for accessing the Russian market.

Getting started

Registering prior to undertaking construction work is relatively simple. The Government Agency for Construction issues three degrees of licenses. The first license is for small projects, the second is for small to medium-sized projects, and the third is for large-scale projects anywhere in Mongolia. As the project develops the company is obligated to notify and allow local building inspectors to enter the site.

Residency Permits

All foreigners wishing to remain in Mongolia for more than 30 days must apply to the State Centre for Civil Registration and Information for a temporary residency permit or a short-term residency permit.

Temporary Residency Permit

The applicant must present to the State Centre for Civil Registration a request issued by FIFTA. FIFTA will issue such a request to any agreed foreign investor immediately. Permits are generally issued within a couple of days and are valid for a period of time from three months to one year. A temporary residency permit can be renewed an unlimited number of times. Each renewal will re-validate the permit for a period from three months up to one year, as requested by the investor.

Short Term Residency Permit

This non-renewable permit is issued to foreigners who plan to spend no more than 90 days in Mongolia. Applicants are required to present a written request from a Mongolian or foreign organization stating the activity in which the person will be engaged and the reason the permit is needed. In case of an exploratory visit by a potential investor, a letter from the home company will suffice.

Entry Visas

Investors may apply for single-entry and multiple-entry visas at the Foreign Ministry’s Chancellery Building in Ulaanbaatar or at Mongolian diplomatic missions in other countries.

Single-Entry Visas

A single-entry visa is valid for three months from its date of issuance and entitles the bearer to enter and stay in Mongolia for 30 days. A letter of invitation or applicable work papers are required. This type of visa is issued at the Ulaanbaatar airport or land border-crossing point.

Multiple-Entry Visa

A multiple-entry visa entitles the bearer to enter and exit Mongolia an unlimited number of times and is valid for a period of six months to one year. For the issuance of this type of visa, an official letter stating the reason for travel and a copy of the certificate of the organization must be submitted by the investor.

(Source: FIFTA)

Infrastructure facts

Airports – Mongolia has 81 airports, of which 31 can be used year-round. Only eight are paved.

Roads and highways – Mongolia has 1,531.7 km paved roads.

Railway – Mongolia has 1,750 km of rail track, mostly a north-south line reaching from Russia to China, with spur lines to the copper mining city of Erdenet and the coal mining city of Baganuur. A short line goes from the eastern city of Choibalsan to Russia.

Registered trucks – 25,473 (1998)

Major infrastructure projects (1997-1999)

USA

Mongolia energy sector project – US $45,500,000

World Bank

Mongolia coal project – US $35,000,000

Transport rehabilitation project – US $32,313,000

Asian Development Bank

Telecommunications – US $24,381,000

Power station rehabilitation – US $38,277,000

Ulaanbaatar heat efficiency project – US $29,487,000

Provincial towns basic urban services project – US $7,695,000

Road development – US $22,499,000

Ulaanbaatar airport project – US $37,524,000

Japan

Road construction (1996) – (Yen) 11,590,000

Rehabilitation of power plant IV (1995) – US $46,000,000

France

Rehabilitation and extension of UB telephone network – (F Franc) 25,000,000

Germany

Telecommunications – (DM) 10,000,000

South Korea

Thermoelectric power plant in the Gobi desert – US $8,000,000

Upcoming major infrastructure projects

Asian Development Bank

Improving Ulaanbaatar heat efficiency (until 2002) – US $39,785,000

Japan

Building of rural schools – US $20,000,000

In 1998 Tg, 208 billion was invested in Mongolia, of which Tg 57.2 billion was on construction/major improvements

Source: State Statistical Bulletin

Construction trends in Mongolia show that in-country production of materials has suffered greatly.

Building doors and window

Tg 417.8 million in 1989

Tg 2.9 million in 1998

Bricks (million pieces)

172.8 (1989)

18.9 (1998)

Cement (in thousand tons)

512.6 (1989)

109 (1998)

On a positive note, sales of furniture went up

Tg 34.7 million in 1989

Tg 185.2 million in 1998

Media Coverage:

Construction Business Review: Creating Overseas Market Opportunities for U.S. Companies

“Support for incoming and outgoing trade missions are among the business outreach and support services offered by the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Global Technology Network (GTN) program. USAID, in turn, draws heavily on expertise from the International executive Service Corps (IESC) in organizing and implementing these trade missions.

“In January 2000, a USAID supported, IESC-assisted, incoming trade mission from Mongolia was instrumental in introducing Mongolian businesses to the American construction industry. Dubbed “U.S.-Mongolian Construct 2000,” the “reverse” trade mission brought representatives from 15 Mongolian construction firms to meet one-on-one with American companies in Dallas, Seattle and Anchorage and Fairbanks, Alaska. The Mongolian trade mission began in Dallas, where the group attended the National Association of Home Builders’ Show (NAHB) – the largest event of its kind in the country. Next, they traveled to Seattle for the Evergreen Gateway Building Products program. In Alaska, the group learned how U.S. construction companies handle building on permafrost and deal with extreme cold weather conditions. According to the U.S. Ambassador to Mongolia, Alphonse F. LaPorta, ‘Mongolia is at the center of a region undergoing substantial infrastructure upgrading, as the market economy takes hold.’”

Update:

https://davidsouthconsulting.org/2021/09/16/case-study-6-international-consulting-1999-2014/

https://davidsouthconsulting.org/2022/02/01/citing-wild-east-the-new-mongolia/

https://davidsouthconsulting.org/2022/04/04/human-development-report-mongolia-1997/

https://davidsouthconsulting.org/2023/01/09/mongolia-update-1998/

https://davidsouthconsulting.org/2023/02/07/mongolian-rock-and-pop-book-mongolia-sings-its-own-song/

https://davidsouthconsulting.org/2022/11/23/papers/

https://davidsouthconsulting.org/2021/05/14/un-ukraine-web-development-experience-2000/

https://davidsouthconsulting.org/2021/11/16/undp-in-mongolia-the-guide-1997-1999/

https://davidsouthconsulting.org/2020/11/05/wild-east-17-years-later-2000-2017/

“I highly recommend Mr. David South as a communications consultant who gets results.” Brian DaRin, Representative/Director, USAID Investment & Business Development Project, Global Technology Network/ International Executive Service Corps-Mongolia, 23 September 1999

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5311-1052.

© David South Consulting 2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.