Paper delivered to the School of Politics and Government, Birkbeck College, University of London, London, UK, 2000

“The strongest is never strong enough to maintain his mastery at all times unless he transforms his strength into right and obedience into duty…Yielding to force is an act of necessity, not of will; at the very most, it is an act of prudence (Rousseau 1762).”

By David South

This paper analyses the following proposition: the key post-war institutions were neither an intended, nor an adequate, response to the economic and political challenges of the post-1945 world.

There is ample evidence to show that the plethora of post-war institutions were intended, and were a deliberate consequence of American policy-makers seeking to control the geo-political fallout of the most catastrophic conflict of human history, World War II.

In many respects institutions such as the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank were a sophisticated and modern approach to a new global order minus the old imperial powers. They were an act of significant imagination and inspiration drawn from a long tradition in asserting the rule of law over the rule of anarchy; the rights of the weak over the tyranny of the strong.

However, these institutions have repeatedly failed to meet the economic and political challenges of the past 55 years. The commitment of the United States to these bodies tailed off after World War II, and America displayed a lack of will to mature them beyond a dependence on American initiative and action.

There is substantial evidence to support the argument that the hegemony of Pax Americana over the last half century undermined the evolution of these institutions, sustaining a chaotic world order that has not delivered prolonged peace or prosperity for a large number of the world’s citizens and that these institutions were ill prepared to confront the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the 1980s.

This paper will explore the inadequacies of the global institutions to meet two key aspirations of the post-war world: conflict resolution and avoidance and economic prosperity based on free markets and democratic regimes.

I will argue that, while this period avoided a major conflagration on the scale of the world wars, it was not a period of peace. Regional conflicts, costly both in terms of human life and of finance, plagued every one of the years since World War II. This has been called a period of Pax Americana (Knutsen 1999). I will argue that, rather than a period of global harmony and prosperity anchored by the American hegemon, it has been a period of Pax Chaotica, a “macabre dance of death in which the rulers of the superpowers mobilize their own populations to support harsh and brutal measures directed against victims within what they take to be their respective domains, where they are ‘protecting their legitimate interests,’” as Noam Chomsky describes it (Chomsky 1995: 207). Pax Chaotica is a period in which there is an illusion of stability offered by a hegemon, but in which the hegemon’s military, economic and moral superiority is unable to secure actual peace and prosperity in the world. The hegemon is out of balance, its military and economic superiority in predominance, while its moral superiority and credibility wanes and withers on the vine.

I will analyse how adequate the global institutions were in the context of the concept of hegemony — in particular the hegemony of the United States, which has not relinquished this hegemony to the global institutions it initially set up. I will conclude that the 1990s has been a period of half measures, incremental attempts at bolstering the concept of international security by the community of nations, but that those attempts, as in the case of the Gulf War or in Kosovo, have been still under the direction of the United States.

Making up a master plan: The deliberate development of the institutions

The post-war master plan was comprehensive, and included the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank), the International Monetary Fund, the International Trade Organisation (superseded by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade as the instrument of freer trade) and the United Nations. A clutch of security organisations was also established after the war, including NATO. As Knutsen aptly puts it:

WITH MEMORIES OF THE INTERWAR RECESSION AND THE NEW DEAL FRESHLY IN MIND, ALREADY, IN THE FIRST YEARS OF THE WAR THEY BEGAN TO DESIGN STABILISING POSTWAR INSTITUTIONS OF INTERNATIONAL FINANCE AND TRADE — THE IBRD, THE IMF AND THE ITO. … THEY SOUGHT TO SET UP THE MOST IMPORTANT POSTWAR INSTITUTIONS BEFORE THE CONDITIONS OF PEACE WERE EVEN RAISED. THEY RUSHED THE CONFERENCES ON THE UN, IBRD, IMF AND ITO INTO SESSION BEFORE GERMANY AND JAPAN SURRENDERED. (KNUTSEN 1999: 203)

The founding of the United Nations and the Bretton Woods institutions (the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, later the World Bank) marked a turning point in world history. The United States had been attempting to exert greater control on the global order since the first 14 proposals of President Woodrow Wilson during World War I. As European powers declined at the beginning of the 20thcentury, liberal American policymakers saw an opportunity for the US to assert its hegemony over the world and re-write the rules of economic engagement along American lines. The two world wars only made the US wealthier and wealthier: in World War I, by providing armaments to both sides of the conflict; in World War II by joining with Canada as the armament and resource engine for the allied war effort.

In many ways, the new institutions represented a forward-thinking and idealistic policy compared to a global order marked by imperial rivalries. It captured contemporary ideas on economic theory, projected a universalist Lockean ideal that all men from all nations are equal, and it was injected with the idealism and energy of the world’s largest democracy and the strongest market economy.

Franklin Roosevelt, like Woodrow Wilson, saw America’s engagement in the world war as a struggle to contain European-style militarism, imperialism and exclusive trade blocs. America’s aim, in both wars, was to preserve the conditions for liberal world order — for a democratic system of politics and an economic system based on free-market principles. Wilson and Roosevelt both sought to liberalize world trade. And they both sought to use America’s leading position in world politics to bring other countries into line with America’s policy. (Knutsen 1999: 193)

These institutions ensured that the US had an influence on every facet of world affairs post World War II. It could merge its political and economic goals and ensure it had a stake in the recovery from the war. This played very well when it came to shoring up domestic support in the United States.

Under a World Bank controlled by Americans, development assistance could be focused precisely where America’s core corporations saw the greatest opportunity. And so long as the recipients of America’s foreign aid used it to buy American exports core corporations could venture into global trade confident of receptive markets. Through such means, the playing field of global commerce was sufficiently tipped in America’s direction so that by the mid-1950s even the National Association of Manufacturers could be persuaded to support tariff reduction. (Reich 1992: 64)

The institutions were philosophically strong, too. Learning from Machiavelli that human relations can be cynical, ruthless and riddled with power agendas, the United Nations offered a peaceful forum to resolve these disputes and a theoretically far more transparent alternative than what had come before. As Weber emphasised, modern states helped to promote capitalist development. With that in mind, the Bretton Woods institutions laid the groundwork for a global financial structure pegged to the US dollar and promoting an American view of free markets.

Hegemony theory and Pax Americana

I argue that these global institutions have shown themselves to be hampered and inadequate when faced with serious political and economic challenges. The root cause is a weakness that is most often cited as their strength: the United States.

Hegemonic stability has been characterised by the emergence of successive dominant liberal powers (Gilpin 1987: 66). What Strange calls “structural power” is essential to the establishment of hegemony over world affairs, since it “confers the power to decide how things shall be done, the power to shape frameworks within which states relate to each other, relate to people, or relate to corporate enterprises (Strange 1998: 25).”

The post-World War II global institutions are an excellent example of the intersection of politics and economy; institutions like the United Nations seek to wield influence in both the political sphere and the economic, most particularly through the Bretton Woods institutions. Hegemonic world order exists, Knutsen suggests, “when the major members of an international system agree on a code of norms, rules and laws which helps govern the behaviour of all. This agreement reflects the rhetorical skills of a particular great power (Knutsen 1999: 49).” This is what happened towards the end of World War II, as the United States wrote the new world order according to its own rules.

As further evidence of US supremacy, the new global rules were constructed so as to force America’s superpower rivals, the USSR and China, to join “its” institutions, not the other way around (though Taiwan stood in for the People’s Republic in the United Nations, against the protests of the USSR, until 1971).

The US became the hegemon because the Soviet Union had very little to offer, either in terms of economic assistance or of political freedoms.

Historians now understand that potential clients encouraged the United States to become a hegemon at the end of World War II: the term “empire by invitation” has come to characterize what happened. The Soviet bid for postwar influence lacked any comparable legitimacy, and so quickly came up against a condition that creates major difficulties for hegemons, which is lack of consent. (Gaddis 1992: 177)

Do as I say, not as I do: The rise and fall of the hegemon’s moral advantage

A large part of the credibility of the US hegemony was bolstered by its moral advantage vis-à-vis other nations. A heady cocktail of democratic freedoms, economic success and military might led many other nations to believe the US and its institutions had got it right where others had failed.

As Strange notes: “President Truman had followed up in his augural address to the Congress with the firm promise of American help to peoples seeking freedom and a better material life. Moral authority based on faith in American intentions powerfully reinforced its other sources of structural power (Strange 1994: 32).”

Supporters of US hegemony, like John G. Ruggie, believe the hegemon must be liberal-minded. Otherwise:

IF THE OTHER STATES BEGIN TO REGARD THE ACTIONS OF THE HEGEMON AS SELF-SERVING AND CONTRARY TO THEIR OWN POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC INTERESTS, THE HEGEMONIC SYSTEM WILL BE GREATLY WEAKENED. IT WILL ALSO DETERIORATE IF THE CITIZENRY OF THE HEGEMONIC POWER BELIEVES THAT OTHER STATES ARE CHEATING, OR IF THE COSTS OF LEADERSHIP BEGIN TO EXCEED THE PERCEIVED BENEFITS. (GILPIN 1987: 73)

The US steadily weakened its credibility and moral advantage in both the areas of conflict resolution and avoidance, and in promoting economic prosperity.

Conflict resolution and avoidance

The US was seen as willing to distort global institutions to fight its ideological — and real — battles with the Soviet Union, and its proxies around the world. The US’s credibility as a promoter of peace and security was severely hampered by the Korean War, the Vietnam War and a dubious record of support for undemocratic regimes and guerrilla movements. These conflicts were intended to “contain” the Soviet Union and the spread of communism and to support regimes that were friendly to free markets. This was played out in a cynical cat-and-mouse game with the Soviet Union, where both sides avoided direct confrontation with each other and used third countries to wage their ideological battles.

Gaddis takes an overly generous view of the Cold War high-wire act, but it is worth being reminded:

BUT THE 1950S AND 1960S DID SEE A REMARKABLE SEQUENCE OF POTENTIALLY DANGEROUS CONFRONTATIONS — DIENBIENPHU, 1954; QUEMOY-MATSA, 1955; HUNGARY-SUEZ, 1956; LEBANON, 1958; BERLIN, 1958-59; THE U2 INCIDENT, 1960; CUBA, 1961; BERLIN, 1961; LAOS, 1961-62; THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS, 1962 — EVERYONE OF WHICH WAS RESOLVED WITHOUT MAJOR MILITARY INVOLVEMENT BY EITHER SUPERPOWER. THE SAME COULD NOT BE SAID OF KOREA IN 1950, OR OF VIETNAM AND AFGHANISTAN LATER ON. (GADDIS 1992: 33)

Other than actually being drawn in as a combatant, as in the case of the Korean War, the UN became more of a sideline observer and critic than a robust resolver of conflicts. The UN was critically flawed from the beginning and abrogated its commitment to collective security. It also proved ineffective when confronted with crisis. As Strange points out, one of the biggest weaknesses in the founding of the UN was the Charter. In Article 2, Paragraph 7, all matters of domestic consideration were the business of a state, and in Article 51 states were allowed to form alliances for individual or collective self-defence, “thus reopening the door to a security structure based on alliances and counter-alliance rather than on collective responsibilities for the maintenance of peace between states (Strange 1994: 52).”

The UN was also hampered from developing a collective security maturity by the Security Council. The five permanent members used the veto to control resolutions, with the USSR and the US the most prolific abusers. The US had a total of 69 vetoes from 1945 to 1994; the USSR had 116.

The fall of the Soviet Union at the end of the 1980s marked the beginning of a new period of instability in large parts of the world. The spotlight is once again on the UN to become an arbiter of conflict; once again it is most active when it is pushed by the United States to act when the US feels there is an interest to be served. This has been the case in the major UN missions in the 1990s, from the Gulf War (oil reserves), to the former Yugoslavia (European security). The UN proved to be ineffective where there was no naked US interest putting pressure on the organisation to act, as in the case of Rwanda. Strange remarks that this has had a demoralising effect on those who seek a security structure upholding international law and the universal rights of man.

The fear that either the world organization would merely be the tool of one or other great power (as indeed it was the tool of the United States in the early 1950s) or that it would be ineffectual — as both the League and the UN have proved to be in the face of grave threats to international peace and order — have been enough to kill any realistic hopes of managing a transition from the present security structure to a multilateral or confederal one. (Strange 1994:52)

Economic prosperity

The second half of the 20th century has been hailed as a period of unprecedented global prosperity. Global gross national product rose from US $300 billion to US $2 trillion from 1945 to 1970 (Reich 1992: 64), though much of this was concentrated in a handful of countries. The major challenge of the 20th century has been the task of spreading prosperity around the world; to more evenly distribute the gains than can be reaped from advances in science and technology. The collapse of the colonial powers left large numbers of underdeveloped nations grappling with independence.

With the collapse of the Bretton Woods arrangements in the early 1970s, and the emergence of deregulation in financial flows in the world, the US abrogated much of its responsibility for micro-managing global development. The market was now to do all the work, and being the modern age, rapid capital flows were to make the market work efficiently.

Like the experience with conflict resolution and avoidance, the economic project has been mixed. A dependence on the market has not avoided a dependence on the economic fortunes of the global hegemon. As the US ship rises and sinks, so does the rest of the world. The Global economic system, Panic notes:

WAS RUN BY THE DOMINANT ECONOMIC POWER AFTER THE SECOND WORLD WAR: THE UNITED STATES. IN THAT SENSE, ITS FORTUNES, LIKE THOSE OF THE CLASSICAL GOLD STANDARD, WERE DIRECTLY LINKED TO THOSE OF THE RELATIVE ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE AND POLICIES OF THE COUNTRY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LARGEST SHARE OF WORLD INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION, TRADE, AND FINANCE AT THE TIME — PRECISELY THE OUTCOME THAT THOSE ATTENDING THE BRETTON WOODS CONFERENCE HAD BEEN ANXIOUS TO AVOID. (PANIC 1995: 46)

By 1994, total world exports were more than 14 times greater than in 1950; output was five times greater than in 1950 (Dicken 1999: 24). But the economic achievements ring hollow if the well-being of the whole planet is taken into consideration. By 1995, 60 percent of the manufacturing in the world occurred in three countries — the United States, Japan and Germany (UNIDO 1996). While manufacturing in developing countries had quadrupled to 20 percent of global output, it was concentrated in a few developing countries with strong ties to the US.

There is a direct connection between US interests and who does well economically. Western Europe was reconstructed rapidly with US money, and Germany became an industrial powerhouse again. The defeated Japan was restored as Asia’s wealthiest nation with American investment and advice. In 1945, 71 percent of world manufacturing was concentrated in four countries. Developed countries were host to 2/3 of foreign direct investment (Dicken 1999: 21). Most FDI is now concentrated in industrial, developed countries.

There is a direct link between the failures of the UN and the global economy. The weakness of the international security arrangements also have an impact on economies. Vast sums of money are re-directed towards weapons purchases and away from human needs. For many smaller economies, this is a punishing drain on national resources and the funds are often borrowed from elsewhere. As Chomsky noted in the 1980s, “The fact is that both of the superpowers — and many lesser powers as well — are ruining their economies and threatening world peace, indeed human survival, by a mindless commitment to military production for themselves and for export (Chomsky 1995: 209).”

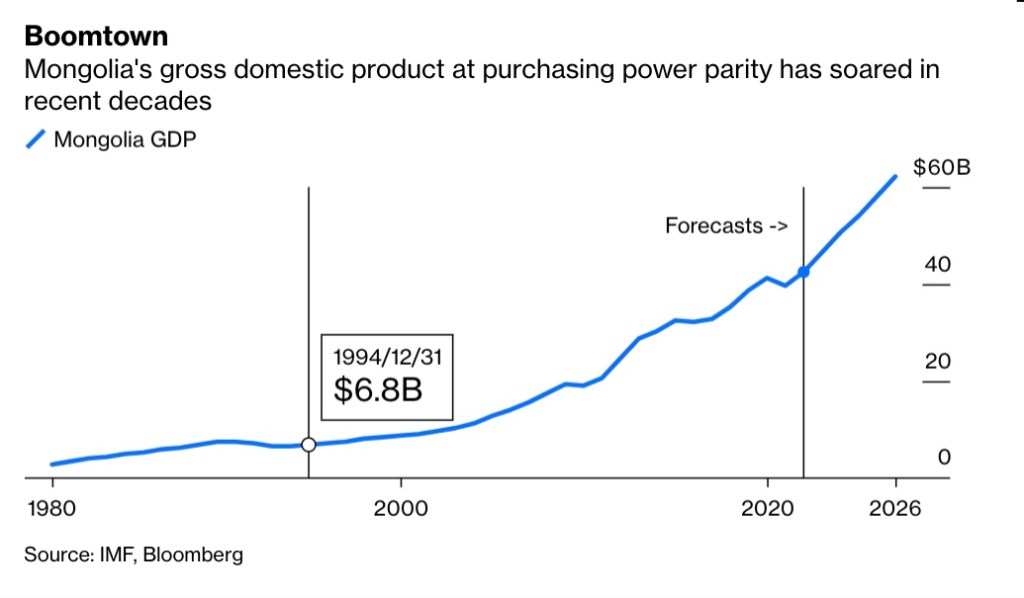

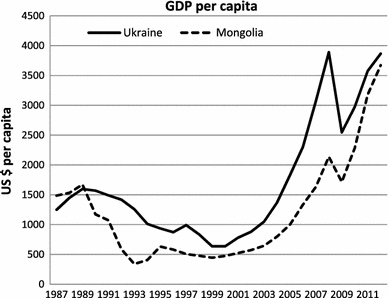

There are concrete examples of developing countries that have achieved significant development gains, reaping the gains of peace and freer world trade. A group of 18 developing countries enjoyed growth rates in the 1990s of over five percent (DFID 2000: 66). This is attributed to more open trade policies compared to other developing countries (though many other countries have been equally open to trade, like Mongolia, but have not reaped the same benefits). China has enjoyed unprecedented growth, but it also has increasing rates of unemployment and violent unrest in its western regions. Sub-Saharan Africa’s 600 million population generates exports no greater than Malaysia’s 20 million (DFID 2000: 67).

In regard to the World Trade Organization (WTO), the majority of its 140 members are developing countries. Not a perfect organisation, its agenda is dominated by a few wealthy nations, but the alternative of a world of bilateral trade deals hangs as a spectre if it fails. As the DFID report, Eliminating World Poverty: Making Globalisation Work for the Poor, points out:

DESPITE PROGRESS OVER THE LAST 50 YEARS, DEVELOPED COUNTRIES MAINTAIN SIGNIFICANT TARIFF AND NON-TARIFF BARRIERS AGAINST THE EXPORTS OF DEVELOPING COUNTRIES…TOTAL DEVELOPING COUNTRY GAINS FROM A 50 PER CENT CUT IN TARIFFS, BY BOTH DEVELOPED AND DEVELOPING COUNTRIES, WOULD BE IN THE ORDER OF $150 BILLION — AROUND THREE TIMES AID FLOWS. (DFID 2000: 69)

Conclusion

The postwar world order and the use of global institutions to build it, was a deliberate policy of the United States. It, however, proved only a half measure and the over-dependence on the United States ensured that these institutions were hampered when confronted with economic and political crises. As I have argued, a state of Pax Chaotica was the result.

For Pax Chaotica to end, there needs to be a renewed effort by the United States to shore up global institutions and to develop a concrete plan to ensure that the global institutions become the global hegemon in every sense of the word. There have been incremental moves in this direction, including attempts to pay dues owed by the US to the UN.

There needs to be a complete shift from the realist American interests of Pax Chaotica to the interests of the community of nations. In fact, there is an opportunity for a convergence of core American values — respect for individual liberty, freedom of expression, democracy — with the goals of the global institutions.

As for international institutions, they must show themselves to not only be just, but also to be seen to be just. Institutions can no longer work in the shadows as they have in the past. Well-educated, wealthy protesters in Western countries will no doubt continue to demand transparency.

In The Interests Of The Exploited?: The Role Of Development Pressure Groups In The UK

A Steppe Back?: Economic Liberalisation And Poverty Reduction In Mongolia

The Sweet Smell Of Failure: The World Bank And The Persistence Of Poverty

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5311-1052.

© David South Consulting 2017

You must be logged in to post a comment.