By David South, Development Challenges, South-South Solutions

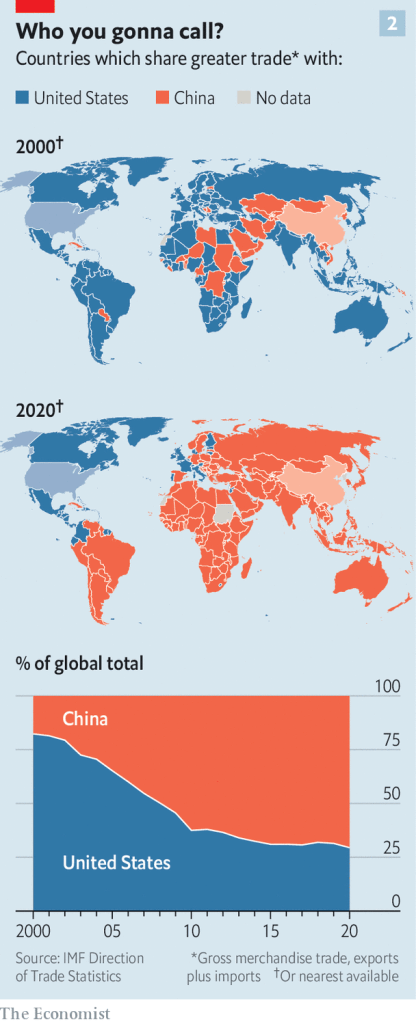

The world is currently undergoing a high-stress transition on a scale not seen since the great industrial revolution that swept Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. Today’s urban and industrial transition involves many more people and is taking place on a greater proportion of the planet. With rapid urbanization comes a demand for middle class lifestyles, with their high-energy usage and high consumption of raw materials.

This is stretching the planet’s resources to breaking point. And as many have pointed out, if the world’s population is to continue past today’s 7 billion to reach 9 billion and beyond, new ways of living are urgently required. Radical thinking will be necessary to match the contradictory goals of raising global living standards for the world’s poor with pressured resources and environmental conditions.

But there are innovative projects already under development to build a new generation of 21st-century cities that use less energy while offering their inhabitants a modern, high quality of life. Two examples are in China and the Middle East.

Both projects are seen as a way to earn income and establish viable business models to build the eco-cities of the future. Each project is seeking to develop the expertise and intellectual capacity to build functioning eco-cities elsewhere. In the case of the Masdar City project in the United Arab Emirates, international businesses are being encouraged to set up in Masdar City and to develop technologies that can be sold to other countries and cities – in short, to create a green technology hub akin to California’s hi-technology hub ‘Silicon Valley’. Masdar City is also being built in stages as investors are found to help with funding. Both projects hope to prove there is money to be made in being green and sustainable.

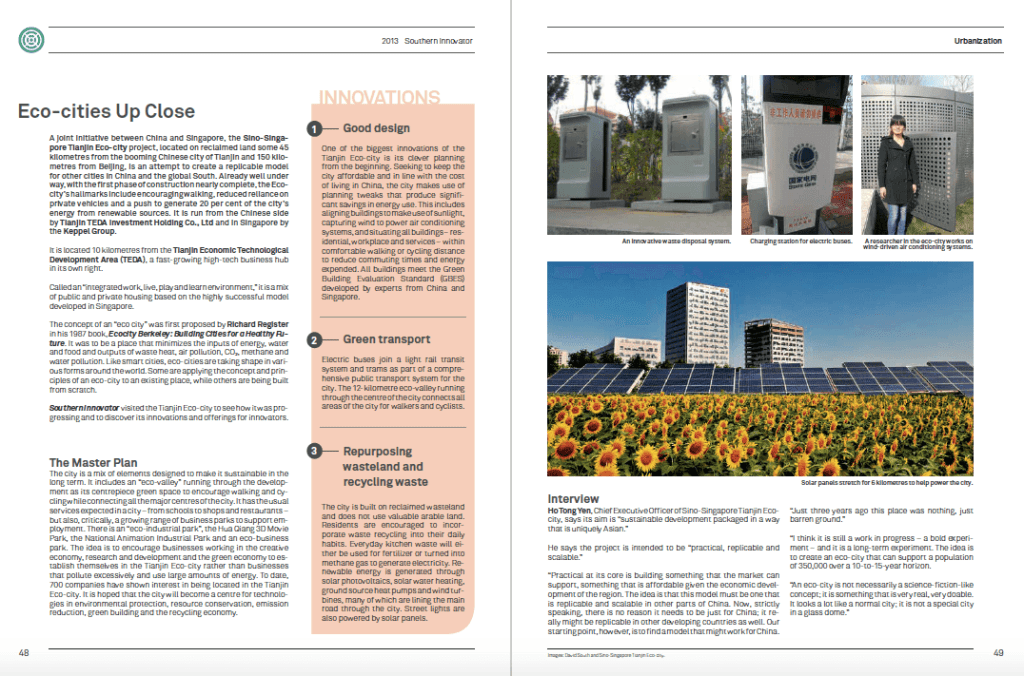

The Tianjin Eco-city (tianjinecocity.gov.sg) project is a joint venture between China and Singapore to build a 30 square kilometre city to house 350,000 residents.

Tianjin (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tianjin) is a large industrial city southeast of China’s capital, Beijing. It is a place that wears the effects of its industrial expansion on the outside. Air pollution is significant and the city has a grimy layer of soot on most outdoor infrastructure.

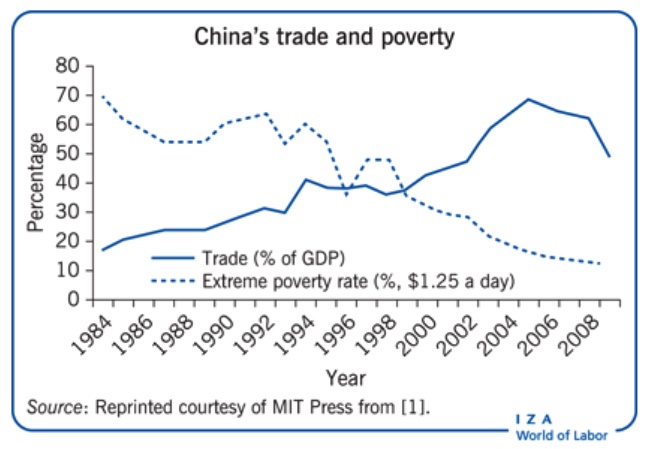

China has received a fair bit of criticism for its polluted cities as the country has rapidly modernized in the past two decades. This sprint to be one of the world’s top economic powers has come at a cost to the environment. In this respect, China is not unusual or alone. Industrialization can be brutal and polluting, as Europe found out during its earlier industrial revolution.

But China is recognizing this can’t go on forever and is already piloting many initiatives to forge a more sustainable future and bring development and high living standards back in line with what the environment can handle.

Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-city is the second large-scale collaboration between the Chinese government and Singapore. The first was the Suzhou Industrial Park (http://www.sipac.gov.cn/english/).The Tianjin project came up in 2007 as both countries contemplated the challenges of rapid urbanization and sustainable development.

The project’s vision, according to its website, is to be “a thriving city which is socially harmonious, environmentally-friendly and resource-efficient – a model for sustainable development.”

The philosophy behind the project is to find a way of living that is in harmony, with the environment, society and the economy. It is also about creating something that could be replicated elsewhere and be scaled up to a larger size.

The city is being built 40 kilometres from Tianjin centre and 150 kilometres from Beijing. It is located in the Tianjin Binhai New Area, considered one of the fastest growing places in China.

Construction is well underway and can be followed on the project’s website (http://www.tianjinecocity.gov.sg/gal.htm). It will be completed in 2020.

This year, the commercial street was completed and is ready for residents to move in.

Residents will be encouraged to avoid motorized transport and to either use public transport or people-powered transport such as bicycles and walking.

An eco-valley runs down the centre of the city and is meant to be a place for pedestrians and cyclists to enjoy.

The basic building block of the Eco-city – its version of a city block – is called the Eco Cell. Each Eco Cell measures 400 metres by 400 metres, a comfortable walking distance. Four Eco Cells make a neighbourhood. Several Eco Neighbourhoods make an Eco District and there are four Eco Districts in the Eco-city. It is a structure with two ideas in mind: to keep development always on a walkable, human scale and also to provide a formula for scaling up the size of the Eco-city as the number of residents increases.

It is a logical approach and seeks to address one of the most common problems with conventional cities: sprawling and unmanageable growth that quickly loses sight of human need.

Agreement was also reached on the standards that should be achieved for a wide variety of criteria, from air and water quality to vegetation, green building standards, and how much public space there should be per person.

An ambitious project in the United Arab Emirates is trying to become both the world’s top centre for eco cities and a living research centre for renewable energy. Masdar City (http://www.masdarcity.ae/en/)is planned to be a city for 40,000 people. It is billed as a high-density, pedestrian-friendly development where current and future renewable energy and clean technologies will be “marketed, researched, developed, tested and implemented.”

The city hopes to become home to hundreds of businesses, a research university and technology clusters.

This version of an eco-city is being built in three layers in the desert, 17 kilometres from the Emirati capital Abu Dhabi. The goal is to make a city with zero carbon emissions, powered entirely by renewable energy. It is an ambitious goal but there are examples in the world of cities that use significant renewable energy for their power, such as Reykjavik, Iceland in Northern Europe, which draws much of its energy from renewables and geothermal sources.

Masdar City is designed by world-famous British architect Norman Foster (fosterandpartners.com) and will be 6.5 square kilometres in size.

The design is highly innovative. The city will be erected on 6 metre high stilts to increase air circulation and reduce the heat coming from the desert floor. The city will be built on three levels or decks, to make a complete separation between transport and residential and public spaces.

The lowest deck will have a transportation system based on Personal Rapid Transport Pods. These look like insect eyes and are automated, controlled by touch screens, using magnetic sensors for propulsion. On top of this transport network will be the pedestrian streets, with businesses, shops and homes. No vehicles will be allowed there, and people will only be able to use bicycles or Segway (segway.com) people movers to get around. An overhead light railway system will run through the city centre, all the way to Abu Dhabi City.

“By layering the city, we can make the transport system super-efficient and the street level a much better experience,” Gerard Evenden, senior partner at Foster + Partners, told The Sunday Times. “There will be no car pollution, it will be safer and have more open spaces. Nobody has attempted anything like this.”

Masdar City is being built in stages as funding comes, with the goal of completion by 2016. It hopes to achieve its aspiration to be the most technologically advanced and environmentally friendly city in the world. As for water supplies in the desert, there is a plan: dew collected in the night and morning and a solar-powered desalination plant turning salt water into drinking water.

Electricity will come from a variety of sources. Solar panels will be on every roof and double as shade on alleyways. Non-organic waste will be recycled, while organic waste will be turned into fuel for power plants. Dirty water will be cleaned and then used to irrigate green spaces. Because of the design, the planners hope the city will just use a quarter of the energy of a conventional city.

To keep the city smart and the project on top of developments in renewable energy, the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology (http://www.masdar.ac.ae/) will specialize in renewable energy technology.

The cost for the city was pegged at US $22 billion in 2009.

The chief executive of Masdar – Abu Dhabi’s renewable-energy company – is Sultan Al Jaber. He sees the city as a beacon to show the way for the rest of the Emirate to convert from a highly inefficient consumer of energy to a pioneer in green technology.

“The problem with the renewable-energy industry is that it is too fragmented,” he told The Sunday Times. “This is where the idea for Masdar City came from. We said, ‘Let’s bring it all together within the same boundaries, like the Silicon Valley model (in California, USA).’”

The project needs to gather much of its funding as it progresses. The United Nations’ Clean Development Mechanism (http://cdm.unfccc.int/) is helping with financing. Companies can earn carbon credits if they help fund a low-carbon scheme in the global South. The sultan is ambitious and sees this as a “blueprint for the cities of the future.” It has been able to bring on board General Electric (GE) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to sponsor the university.

It is possible to visit Masdar City and take a tour (http://www.masdarcity.ae/en/105/visit-masdar-city/) and it is also possible to view online what has been built so far (http://www.masdarcity.ae/en/32/built-environment/).

Published: June 2012

Resources

1) Center for Innovation, Testing and Evaluation (CITE): Located in Texas, USA, CITE is a fully functioning city with no residents to test new technologies before they are rolled out in real cities. Website: http://www.pegasusglobalholdings.com/test-center.html

2) Digital Cities of the Future: In Digital Cities, people will arrive just in time for their public transportation as exact information is provided to their device. The Citizen-Centric Cities (CCC) is a new paradigm, allowing governments and municipalities to introduce new policies. Website: http://eit.ictlabs.eu/action-lines/digital-cities-of-the-future/

3) Eco-city Administrative Committee: Website: http://www.eco-city.gov.cn/

4) Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-city, Investment and Development Co., Ltd. Website: tianjineco-city.com

5) ‘The Future Build’ initiative, a new green building materials portal from Masdar City. Website: thefuturebuild.com

6) UNHABITAT: The United Nations Human Settlements Programme is the UN agency mandated to promote socially and environmentally sustainable towns and cities with the goal of providing adequate shelter for all. Website: http://www.unhabitat.org

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5311-1052.

© David South Consulting 2022

You must be logged in to post a comment.