Paper delivered to the School of Politics and Government, Birkbeck College, University of London, London, UK, 2000

“… aid is no longer charity. It has become intrinsic to the maintenance of the international capitalist economy … (Fieldhouse 1999).”

By David South

In January 1949, US President Harry Truman set forth a challenge for the remainder of the 20th Century: the wealthy nations must aid the poorer ones to become wealthier and more democratic: in short, to become like the United States (Starke 2001: 143). The means of accomplishing this was to be international development, and its tool, foreign aid.

Decades later, this dream was being described as a nightmare. One of the most articulate proponents of the aid-is-waste thesis is Graham Hancock. His Lords of Poverty comes down unequivocally on the side of failure. Hancock argues that aid “is a waste of time and money, that its results are fundamentally bad, and that – far from being increased – it should be stopped forthwith before more damage is done (Hancock 1996: 189).”

Hancock originally wrote those words in 1989. Subsequently, a decade has past where international development organizations have attempted to prove the success of development in a wider context of the collapse of the Soviet Union, a crippling economic crisis in Asia and the former Soviet Union, and dizzying changes in information technologies. In addressing the proposition that “by the end of the 20th century, ‘development’ had failed”, it is important to clarify the underlying intentions of interntional development and whi the true actors are, and the interaction of politics and economy.

This paper will focus on one actor, the World Bank, which has seen itself as the principal international development organization for the past 55 years. I argue that the World Bank has been very successful at building a dependence on development institutions, itself in particular, but has failed at development as it has defined it: the elimination of poverty. The four main power structures underpinning the world economy described by Susan Strange – security, production, financial, and knowledge (Strange 2000: 43-119) – are each addressed by the World Bank’s programmes to varying degrees of success. It is the World Bank’s interaction with these power structures that have been a source of both stability and instability in the past 55 years.

I have chosen the World Bank because, as Hancock notes, it is

The pace-setter of Development Incorporated … the fact is that all official aid agencies, whether bilateral or multilateral, co-operate very closely with it, imitate its policies and its sectoral priorities and, to a large extent, share what might be called its ‘philosophy of development’. (Hancock 1996: 57)

I conclude that international development is now entering a new phase spurred on by the economic crisis affecting many developing nations after 1997, and not facing its destruction, in spite of rowdy protests around the world. The Asian Crisis provoked an increase in development spending, while simultaneously significantly raising awareness of international development institutions. At the beginning of the 21st century, the rise of the non-governmental organization as a key actor in development is strongly pronounced.

The fact that NGOs and private consulting companies are becoming the principal delivery mechanisms for development projects demonstrates a global lack of faith in government-run agencies and a belief in neo-liberal assertions that the private sector can do a better job.

1. Development: pernicious or persistent?

The word development needs to be pulled apart. Its endurance as a concept comes down to its ability to mean many things to many people. It is a loaded word, which upon closer inspection, becomes befuddingly vague and as slippery as an oil-soaked eel.

Development as defined by President Truman at the start of the development period of the 20th century meant “nothing less than freeing a people from want, war, and tyranny, a definition it is hard to improve on even today (Starke 2000: 153).”

Dictionary definitions of development take in ideas of growth, progress and evolution. As Hancock noted in Lords of Poverty, “underdevelped” countries “must in some sense be stunted and backward; ‘developed countries’, by contrast, are fully grown and advanced (Hancock 1996: 41).” Hancock bristles at the moralistic notion that particular countries may need to develop; in this he would probably have clashed with Marx, as Fieldhouse notes: “much as he hated capitalism, Marx saw it as a necessary agency for creating what we now call development in India and, by inference, most parts of the Third World (Fieldhouse 1999: 44).”

A refinement of this definition is one offered by the World Bank’s president in the 1980s, Barber Conable. Development offers measures “to promote economic growth” and “combat poverty”; those are the “fundamental tasks of world development” with the World Bank being the “world’s principal development agency” (Hancock 1996: 41).

More recently, in answer to heated criticism from donor nations and powerful NGO lobbies, the World Bank has adopted a more urgent tone on poverty. “Poverty reduction is the most urgent task facing our world today. The World Bank’s mission is to reduce poverty and improve living standards through sustainable growth and investment in people (World Bank 2000).”

Assessing development according to the World Bank’s definition of development, with its focus on eliminating poverty, it is very hard to say this has been a success, as I show further on.

2. Failure thesis: why the World Bank is a flawed poverty-fighter

The notion that development has failed has its critics on both the left and the right. On the right, development is seen as state welfare, bailing out countries that need to get their own houses in order. On the left, development has been seen, variously as a tool of the wealthy states to control the poorer states, a means to prop up corrupt but friendly elites, environmentally destructive, and a subsidy system for multinationals. Marxists have straddled the contradictions of criticising the effects of development while also chastising the wealthy West for not doing enough for the developing nations.

Since 1990 World Bank cumulative lending has totalled US $162,789.3 million (World Bank Annual Report 2000). Since its inception, global aid has risen from US $1.8 billion a year in the 1950s, to US $6 billion in the 1960s, to US $60 billion in the 1980s, to where it currently stands at US $129.2 billion (World Development Indicators Database). The Bank disburses US $25 billion a year (World Bank). Vast amounts of money is flowing back to the West in the form of payments on debts nearly totalling US $3 trillion (Starke 2000: 153).

In fact, the World Bank through its lending wings, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Development Agency (IDA), embodies an inherant contradiction: it has shown itself to be unable to decouple its mandate to recover funds from what might be the wiser strategy. As the Bank puts it, “while the country must “own” its vision and program, the Bank must “own” and be accountable to shareholders for its diagnosis and the program it supports (World Bank).”

Over the development epoch, loans were accepted by countries that have shown themselves to be incapable of repayment, leading to the debt crisis today. While this crippling debt has been accumulated, the world has come no closer to eradicating poverty.

A brief look at the figures shows the scale of the challenge. Development policies have not been able to come to grips with escalating population rates in developing nations. During the period of development, the population of the regions with the lowest rates of development have risen rapidly. As Strange notes:

World population doubled between 1950 and 1984, rising rapidly from 2.5 billion to over 4.5 billion and topping 5 billion by the end of the decade… Numbers have increased most dramatically in the three ‘developing’ regions of Latin America, South Asia and Africa … (Strange 2000: 82)

Aid on the macro scale is also unequally divided, with the 10 countries that two-thirds of the world’s poor live in receiving less than a third of overseas development aid (Raffer and Singer 1996). And when it arrives in a country very little of it gets into the hands of the poor. Some generously claim that 20 per cent of aid reaches the poor (Raffer and Singer 1996), while Hancock maintains even less wends its way to the poorest.

According to the United Nations Development Programme, more than 1.3 billion people live on just US $1 a day; and 2.8 billion live on US $2 a day – nearly half the world’s population (UNDP). This number has remained unchanged since 1990 (Starke 2000: 4). In fact, in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and the former communist countries, “the number living in poverty is substantially higher than the figures recorded a decade ago (Starke 2000: 4).” The most noted trend is the diffusion of poverty and its more pronounced ability to sit side-by-side with an economic boom in developing – and developed – countries, fuelled by increased investment, especially in the areas of information technology and telecommunications.

The World Bank has set the target date of 2015 to cut extreme poverty by half. It remains highly dubious as to how the World Bank has any better idea of how to do this than it did in the first 55 years of development theory and practice. Theories have been misguided in the past, as Fieldhouse reminds us:

Central to all post-1950 attitudes to Third World development was the belief that the primary need was capital investment. The defining feature of underdevelopment was thought to be lack of sufficient capital to pay the cost of overcoming the perceived ‘structural’ obstacles to development. A short shopping list of what were then believed to be the necessary measures would include the following: first, the improvement of infrastructure – communications, power and water supplies, urban facilities and hospitals; secondly, education to raise the general level of literacy and to generate skilled workers at all levels, from the highest posts in government and industry, which was believed to be the basis of western affluence and must therefore become that of the Third World. (Fieldhouse 1999: 226)

It has been a period noted by a belief that development could be accelerated, and that the conditions necessary for development were understood and all that was necessary was capital and will.

In fact international development, when it has intended to eliminate poverty, has been unable to detatch itself from what can only be called the whirlpool effect, or the core-periphery debate: a tendency for wealth and power to be dragged into the centre, like a whirlpool: to wealthier nations, wealthy elites, capital cities. While aid is ostensibly about countering this trend, it fails miserably at doing it. The continent that requires the most aid, Africa, receives the least – in the 1990s the World Bank lent Africa a total of US $1,872.8 million (World Bank). It lent Latin America and the Caribbean US $51,520.8 million (World Bank). If, as Truman said, development is about helping those suffering from want, war and famine, then Africa is being ill served.

Looking at the evidence, it shows that aid follows the same pattern as private investment, seeking out success stories, rather than the poor, who by definition are society’s losers. It is an established fact that most trade flows and foreign direct investment is between the wealthy countries (Hirst and Thompson 2000: 2). The percentage of world trade captured by the developing countries has dropped from 50 per cent in the 19th century to 22 per cent (Hoogvelt 1997: 14). It is this tendency that builds into international development a peripherising effect that leaves billions on the outside of development and wealth acquisition – and draws the criticism that development has failed at its principal aim, as the World Bank puts it, to reduce poverty.

3. Security/production

Strange has noted where power lies in the modern world. Those who can influence or determine the structures of power will wield enormous influence over economic and political relations. The World Bank is an institution that has had a profound effect on the power structures of the world economy, with positive and negative consequences.

Security is the “provision of security by some human beings for others (Strange 2000: 45).” Strange focuses on the state as the primary provider of this security in the current international political system. She also broadens this definition to include “security from slow death by starvation, and security from disease, from disablement, or from all sorts of other hazards – from bankruptcy to unemployment (Strange 2000: 47).” And she attributes most conflict to disagreements over authority.

One of the biggest challenges now facing developing states is that of authority over their affairs. It is a two-pronged challenge, from outside and from within, as much of development aid now targets NGOs and civil society.

It is arguable that the World Bank’s greatest contribution to a state is its advice on governance, legislation and anti-corruption. While the World Bank is not tasked with a specific security mandate, it does play a significant role in supporting the viability of nation states, and offers up an off-the-shelf range of authoritative institutions that nation states are advised to take up. Through Structural Adjustment Loans (SAL) and their equivalents, countries are persuaded to adopt these measures or face losing the lifeline of funds.

These policies also dovetail with global concerns for security and stability, in terms of the absence of conflict and also in terms of predictability. Other governments will feel more comfortable dealing with philosophies and institutions that ring of familiarity. But how susccessful has the World Bank been?

Evidence has shown that the SAL loans and their package of reforms were destabilizing and inherently contradictory. As Hoogvelt illuminates:

they sought to denationalize the economies themselves by imposing various forms of deregulation, liberalisation and privatisation, indeed the dismantling of the public sector … At the ideological level it made the bailiffs walk a tightrope between, on the one hand re-affirming the notions of national sovereignty and national economy, while at the same time, and on the other hand, confining development economics and any hint of Keynesian notions of national economic management to the dustbins of history. They had to uphold the state and destroy it at the same time! (Hoogvelt 1997: 167)

The results have actually jeopardised security within Africa, and according to Robert Kaplan, the chaos on that continent will wreck havoc outside Africa as well (Kaplan 1994). Security is probably the World Bank’s greatest failure in the four global power structures. Hoogvelt concludes that its legacy in Africa is particularly disturbing:

In many African countries, the imposition of the neo-liberal orthodoxy, including privatisation of the public sector, the emasculation of the state apparatus and the insistence on electoral reform, has directly contributed to the descent into anarchy and civil wars. (Hoogvelt 1997: 175)

Production as Strange states it, is “the sum of all arrangements determining what is produced, by whom and for whom, by what method and on what terms (Strange 2000: 64).” Production is a bright spot for the World Bank, in that conventional economic statistics have shown a growth in production (even after the 1997 Asian crisis), fuelled by increasing investments in telecommunications, information technologies and greater investment in public utilities (Hirst and Thompson). The World Bank has also an extensive history funding infrastructure projects critical to the functioning of a modern economy, including roads, dams, airports, and ports. There is an extensive literature on the corruption and inefficiency of many of these projects, but at a minimum infrastructure was built.

The World Bank has been “able to profoundly affect the organisation of production and trade in the periphery to the benefit of the core world capitalist system (Hoogvelt 1997: 166).”

During the World Bank’s tenure, foreign direct investment has gradually increased for these states, but because of an intensification of trade between the wealthy nations, the global distribution of GNP has,

changed little over the 1970s and 1980s, and indeed became more unequal rather than less after the 1970s. What all this shows goes against the sentiment that benefits will ‘trickle down’ to the less well-off nations and regions as investment and trade are allowed to follow strictly market signals. (Hirst and Thompson 1999: 71)

At a minimum, links have been built and could be the basis of a re-alignment of the world economic order under fairer terms. Hoogvelt notes the links are unquestionably tight:

Structural adjustment has helped to tie the physical economic resources of the African region more tightly into servicing the global system, while at the same time oiling the financial machinery by which wealth can be transported out of Africa and into the global system. (Hoogvelt 1997: 171)

4. Financial/knowledge

Strange calls financial power the ability to “create credit”. It “implies the power to allow or to deny other people the possibility of spending today and paying back tomorrow, the power to let them excercise purchasing power and thus influence markets for production, and also the power to manage or mismanage the currency in which credit is denominated (Strange 2000: 90).”

The World Bank’s vast lending capabilities, as shown earlier, means the Bank literally has the power to switch the lights on or off in a country’s economy. It has also been in the forefront of creating today’s “casino” economy, as Strange calls it, the 24/7 financial markets. It has served the interests of the core economies in this arrangement, as Hoogvelt elaborates:

In a world economy dominated by global financial markets, by money careening around the globe at a frenetic pace, the principal national economic objective of the core countries has to be, and indeed has become, one of maintaining the competitive strength of their currency vis-a-vis each other, fighting domestic inflation that threatens this competitive strength, and trying to catch as much as possible of the careening capital flows into the net of their domestic currency areas. (Hoogvelt 1997: 165)

As Fieldhouse reminds us, “In the later twentieth century, in fact, the World Bank and the IMF were the main proponents of free trade and other related principles in the less-developed world. They thus filled the same role as Britain had done a century earlier (Fieldhouse 1999: 20).”

After World War II, it became apparent the world financial system was not going to be able to function with a hands-off United States. The Marshall Plan in Europe established the precendent of significant loans to aid countries to economically “recover”. As these two influential World Bank economists wrote, it was partly about creating conditions amenable to investors’ interests: “Thus, basic fiscal and monetary discipline, including a properly managed exchange rate, helps establish the credibility of economic policy that gives entrepreneurs the confidence to invest (Stiglitz and Squire 2000: 386).”

And they confirm the whirlpool effect: “Entrepreneurs will not invest in countries where the policy regime is unstable – investors require a degree of certainty (Stiglitz and Squire 2000: 386).”

The World Bank since 1996 has called itself the “Knowledge Bank”, because “We live in a global knowledge economy where knowledge, learning communities, and information and communications technologies are the engines for social and economic development (World Bank).”

In many respects, the World Bank has defined development as most people understand it. As Hancock reminds us, “Consciously or unconsciously we view many critical global problems through lenses provided by the aid industry (Hancock 1996: xiv).” Knowledge and intelligence-gathering is key in an age dominated by information. As Clark notes of development organizations,

The ‘software’ of their trade – ideas, research, empowerment, and networking – are rapidly becoming more important than their ‘hardware’ – the time-bound, geographically fixed projects, such as wells and clinics. In this new age, information and influence are the dominant currencies rather than dollars and pounds. (Clark 1992: 193)

The vast volume of statistics and reporting produced by the Bank on the global economy is valuable and it is frequently used as a source even by its critics. This quite possibly is the Bank’s greatest success. The Bank’s focus on information technologies is also valuable and it is aiding developing countries around the world to gain access to the internet for example. Keohane notes that information by its very existence can generate greater cooperation between states:

Informaton, as well as power, is a significant systemic variable in world politics. International systems containing institutions that generate a great deal of high-quality information and make it available on a reasonably even basis to the major actors are likely to experience more cooperation than systems that do not contain such institutions … (Keohane 1984: 245)

Conclusion

Like a chameleon, the political and economic actors in development change their appearance according to evolving conditions. I have argued in this paper that the fundamental needs – a desire for markets, global interconnectivity and political control – ensure the World Bank’s role in international development remains principle to the day-to-day lives of developing countries. It is also a fact that development organizations such as the World Bank have amassed a wealth of knowledge and expertise that binds donor nations to them, though this is being supplanted by NGOs as they in turn create a dependency between themselves and the World Bank.

The World Bank’s greatest success has been the perpetuation of the development industry and its role vis-a-vis the global power structures. It is particularly remarkable that development aid has been so robust for such a lengthy time, and points to the key needs in the power structure that it fulfils. However, the World Bank has failed to significantly reduce poverty in the world, and since it defines development as principally poverty reduction, its form of development has failed.

Development aid in and of itself is a highly successful formula, as attested by the boom currently experienced by NGOs. The trend towards these new actors is well advanced, as The Economist noted: “NGOs have become the most important constituency for the activities of development aid agencies (The Economist 2000: January 27).”

Even more compelling, “Between 1990 and 1994, the proportion of the European Union’s relief aid channelled through NGOs rose from 47% to 67%. The Red Cross reckons that NGOs now disburse more money than the World Bank (The Economist 2000: January 27).”

Unfortunately, there seems to be little evidence that any organization working in development will be out of a job by 2015. In the meantime, the poor remain peripheral actors in a play staged for the benefit of those who are not poor. As Fieldhouse notes:

Thus aid is no longer charity. It has become intrinsic to the maintenance of the international capitalist economy, a system by which western governments directly or through multilateral agencies, mobilize debtors so that they can continue to meet their obligations to both public and private creditors. (Fieldhouse 1999: 253)

More Papers

Pax Chaotica: A Re-evaluation of Post-WWII Economic and Political Order

In The Interests Of The Exploited?: The Role Of Development Pressure Groups In The UK

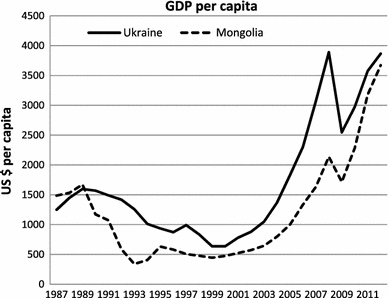

A Steppe Back?: Economic Liberalisation And Poverty Reduction In Mongolia

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5311-1052.

© David South Consulting 2017

You must be logged in to post a comment.