A Partnership for Progress: The United Nations Development Programme in Mongolia

Editor: David South

Publisher: UNDP Mongolia Communications Office

Published: 1997

Background: The Partnership for Progress brochure raised the curtain on UNDP’s programme in Mongolia and my work heading UNDP Mongolia’s Communications Office. I led the Office from 1997 to 1999, garnering awards and praise for the quality of the offline and online resources.

A Partnership for Progress

“For years we were under the domination of foreign countries. So really, Mongolia is a new nation.” With these words, Prime Minister M. Enkhsaikhan described the enormity of the task ahead for Mongolians. While Mongolia has been an independent nation for most of this century, this has not been the case with its economy. Just as a new democratic nation was born in the 1990s, so Mongolia’s economy lost the large subsidies and trading arrangements it had in the past with the Soviet Union. The time to learn about free markets and the global economy had arrived.

Under socialism, Mongolia was dependent on the Soviet Union. Prior to the socialist revolution in 1921, the country experienced hundreds of years under the influence of the Chinese. It is only since 1990 that Mongolia has had an opportunity to build the foundations of an independent economy and political culture. But it takes money and know-how to make the transition work. This is the kind of nation-building support the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) specializes in. UNDP’s fifth country plan for Mongolia has come to an end, and in cooperation with the Mongolian Government the sixth – the Partnership for Progress – has begun.

Meeting the challenges of transition

The international community rapidly responded to Mongolia’s needs in the early 1990s. Along with the large international donors, the UN system is playing a pivotal role with UNICEF, UNFPA, WHO and UNDP to assist in the country’s social reconstruction. Other agencies now operating in Mongolia include UNESCO, UNV, UNHCHR, World Bank and the IMF. The UN’s capacity to coordinate, not only within the UN family of organizations, but also with donors and the international NGO community has proved extremely useful in mobilizing the technical assistance needed at this critical time. The goal is capacity building, or the transformation of both the human and economic resource base to fit the economic and social demands of transition.

UNDP’s Partnership for Progress with the Government of Mongolia serves as the framework for assisting the Government to combat the worst effects of poverty and social disintegration brought on by economic transition. The programmes and projects mounted with UNDP assistance not only tackle the lack of material resources, but also the dearth of practical experience in the strategies and methodologies required to nurture open government and encourage democratic procedures, protect human rights, preserve the environment and promote the private sector.

Mongolia is a large country with poor infrastructure. This means it is not only difficult to transport food or make a phone call, but also to develop and deliver programmes that reach the entire country. It is through the expertise of the UNDP, drawing experience from around the world, that these obstacles to a market economy and an open democracy can be overcome.

UNDP has had a country office in Mongolia since the 1970s. UNDP’s resource mobilization target for the five year programme from 1997 to 2001 is US $27.5 million, with 45 percent to be directed to poverty alleviation, 30 percent to governance and 15 percent to environmental protection. With this material input and the goodwill it generates, the Mongolian Government can design appropriate social and political structures to support their efforts in seeking lasting solutions to the problems brought on by transition. Mongolia can then become an equal player in the global community of the 21st Century.

UNDP in Mongolia

The UNDP’s programmes in Mongolia follow the global principle of helping people to help themselves. Through a close working relationship with the Mongolian Government (the Partnership for Progress), UNDP personnel work with many thousands of Mongolian counterparts in government, academia and NGOs all over the country. In addition, UNDP has a large contingent of United Nations Volunteers (UNVs) deployed in Mongolia. There are over 27 international UNVs working in all UNDP programme areas and further 26 national UNVs working as community activists to foster participation in the poverty alleviation programme. Another six national UNVs are involved in the UNESCO/UNDP decentralization project.

A peaceful transition

The transition in the 1990s from socialism to democracy and free markets has profoundly transformed the country’s political and economic character. Mongolia is a young democracy that is also a model for bloodless political revolution. Today, this participatory democracy boasts scores of newspapers, dozens of political parties and a vigorous parliamentary system. On the economic front, a command-based economy has been replaced by free markets. But there has been a high price to pay in social disintegration and dysfunction, as the former social supports disappear and their replacements fail to “catch” everyone. As with all social upheaval, vulnerable groups – the elderly, the young, the weak – bear the brunt of the social and economic shocks as the old gives way to the new.

The bubble bursts

Before the 1990s, the Mongolian economy was totally dependent on subsidies from the Soviet Union. The state owned all means of production and private enterprise was foresworn. Farmers and herders were organized into cooperatives. Factories had more workers than they needed. Wages were low but no one starved. The state provided for the basics of life – health care, education, jobs and pensions. Free fuel was provided to get through the severely cold winters, and during blizzards lives were saved in stranded communities with food and medicine drops by Russian helicopters.

The bubble burst in 1991 when the Soviet Union disintegrated and the subsidies came to an end. Prior to this, communist countries accounted for 99 percent of Mongolia’s imports and 94 percent of its exports. Mongolia’s economy suddenly lost its buttress and immediately collapsed.

A sense of freedom

Although the economic picture was bleak, politically Mongolians rejoiced and embraced the principles of Western parliamentary democracy. A new sense of political and personal freedom took hold. Freedom of religion ensured a revival of Buddhism. Monasteries sacked and razed under the Communists were restored and religious observance once again became part of daily life.

Collectivization began to give way to free markets and privatization. A voucher system was used to redistribute the assets of many state-owned entities. Each citizen was issued with vouchers to the value of 10,000 tugrigs (at the time worth US $100). They could be bought and sold like shares of stock.

Livestock was privatized and previous limitations regarding ownership of animals were lifted. As a result, the composition of herds changed and the numbers of animals soared to the highest levels in 50 years. While the collapse of the state sector has led to severe hardship, many nomadic herders who astutely manage their herds are self-sufficient in meat and milk. Many continue the old energy saving ways, including collecting dung for fuel and using their animals for transport. Some find it possible to live almost completely outside the cash economy.

Transition shock

The spectre of the worst aspects of market economies soon loomed for many who had known only a poor but predictable life under a command economy. Suddenly unemployment, inflation and reduced services became the norm. Previously reliable export markets in the newly constituted Commonwealth of Independent States disappeared entirely, leaving a ballooning trade deficit and a plummeting tugrig. The fall in global prices for cashmere and copper have only exacerbated an already critical situation.

Poverty strikes

Poverty and starvation hit with a vengeance. According to Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) figures, a third of the population now lives at starvation levels. The demise of collectivized farming has contributed to both a shortage of food and reduction in food self-sufficiency. Thousands of homeless children work, beg or steal in the streets of the capital, Ulaan Baatar. Many descend into the sewers for warmth to escape the subzero temperatures that prevail for most of the year, while others seek refuge in the few children’s shelters in the city.

Unemployment is high. Women are particularly vulnerable, with more than 100,000 summarily removed from the pension rolls at the beginning of 1997. The retired, whose pensions have decreased dramatically in value are also in severe distress, with almost all relying on their families, friends and neighbours. Those without such support are left to live a precarious existence.

Poverty alleviation

To reverse a rapidly deteriorating situation, the Government instituted a six-year National Poverty Alleviation Programme (NPAP) with the primary objective of reducing poverty by 10 percent by the year 2000. Designed with assistance from UNDP, donors and Mongolian NGOs, the NPAP is founded on new principles unseen before in Mongolia. Responsibility is decentralized, with each of the 21 aimags (provinces) having a local Poverty Alleviation Council with responsibility for identification, formulation and appraisal and approval of projects. Thus the people of the area can respond to local needs – identify them, propose solutions to problems and act to determine their own futures.

The Mongolian National Poverty Alleviation Programme addresses a wide range of social issues, including income poverty and the crisis in the health and education sectors. Solutions to such urgent social welfare problems are a high priority for the Mongolian Government – and international assistance is critical. The introduction of fees for health and education services that were previously free has placed an unbearable financial strain on some families. School drop-out rates and truancy are problems in both urban and rural areas. The costs associated with general maintenance and heating of public buildings adds another financial burden in the transition period.

Emphasis on women

A US $10 million soft loan from the World Bank for the period 1996 to 1999 supports Mongolia’s efforts to follow up on the commitments of the World Summit for Social Development, the Fourth World Conference for Women and other recent global initiatives.

The NPAP institutional framework focuses on explicit measures to alleviate poverty by attending to sustainable livelihoods, employment creation, gender equality, grassroots development and human resource capacity building. Mongolia’s historically high levels of literacy, health care and education auger well for the future of this approach, in spite of the many obstacles facing the people.

In addition, the Women’s Development Fund and the Social Assistance Fund have mobilized national NGOs and international donors for both income generation schemes and distress relief for the vulnerable. The success of women in actively implementing projects with the help of the various funds is a testament to the strength and resilience of ordinary Mongolians.

Working with the National Poverty Alleviation Programme initiatives, the UN System Action Plan and Strategy provides technical assistance and capacity training to realize the objectives of the national programme.

In all, eight new projects are on the agenda for 1997, including credit provision, skills and vocational training, water and sanitation provision, urban renewal, pre-school education and one capacity building project at the institutional level.

Freedom of information

Under the Partnership for Progress, UNDP is working with donors and international NGOs to promote and foster a participatory democracy. A key component of good government and democracy is the free flow of information. That is why UNDP has placed a significant portion of its resources into ensuring government, NGOs and citizens have access to the state-of-the-art computer communications technology, especially the Internet and e-mail. The Governance and Economic Transition Programme will have nine new projects by the end of 1997: seven to support national reforms in government and the civil service, two to support journalists as they come to grips with their new responsibilities in a democratic society, and one in the tertiary education sector, following a series of faculty-strengthening education projects that have been ongoing since the early 1990s.

The Consolidation of Democracy through Strengthening of Journalism project offers direct support to working journalists.

Six journalism centres throughout the country offer hands-on training courses and access to news and information from international and Mongolian sources.

At the aimag level, Citizen Information Service Centres will be custom tailored to the information needs of each aimag’s residents. These centres will increase the free flow of information from the capital, which is currently hampered by poor communications infrastructure.

Decentralization, governance and economic transition

The Government has wisely foreseen the need to engage in a fundamental shift in how Mongolia is governed. Not only should it provide institutions that can address the social and economic shocks of the 1990s, but it also must provide a stable and efficient policy to ensure a prosperous and secure future for Mongolia.

Decentralization in government administration is a cornerstone of the Government’s policy to make managers of public services more responsive to local people’s needs. In an ambitious programme to decentralize and consolidate democracy in Mongolia, the Government has promised to devolve decision-making more and more to the local level. The UNDP plays a key role in ensuring this process continues and that local politicians acquire the skills necessary to handle these new responsibilities.

A respect for nature

Mongolia’s flora, fauna and unspoiled landscapes are at a watershed. Mongolians have traditionally had a respect for the natural environment as a source of food and shelter from the harsh climate. These close ties have meant that environmental preservation and respect for nature form an integral part of cultural traditions. As far back as the reign of Chingis Khan in the 13th century, Mongolia has had nature reserves. The new social and economic imperatives have put a strain both on these traditions and the environment, with a corresponding stress on Mongolians.

Semi-nomadic herding still forms the backbone of the country, and the pressures of the 90s have only re-enforced this. Many Mongolians have turned to herding as the only guarantee of a steady supply of food and economic well-being.

The environment is regularly challenged by natural disasters. In 1996, a rash of forest fires destroyed large swathes of land and caused extensive economic and environmental damage. Floods, heavy snowfall, extremely low temperatures, strong winds, dust storms, and earthquakes are all natural hazards for Mongolia.

Keeping Mongolia green

UNDP’s mandate in environmental protection and preservation is reflected in its support to the Government. As Mongolia addresses the challenge of up-holding international conventions to which it is signatory, it must sustain and preserve a decent and dignified lifestyle for all its citizens.

In the area of disaster management, the Government is emphasizing preventative measures as much as relief. UNDP support is focused on an extensive campaign for preparedness, technical support and capacity building to deal with both natural and man-made disasters.

The flagship programme for the environment is the Government’s Mongolia Agenda for the 21st Century (MAP 21). The Government’s continuing biodiversity programme, under the auspices of the Global Environment Fund (GEF), has already shown results, with the on-going mapping of the country’s biodiversity for future generations.

Two new projects were initiated in 1997: the Sustainable Development Electronic Information Network reaches out to people in remote and isolated locations. The Energy Efficient Social Service Provision Project has introduced straw-bale construction, an environmentally-friendly, energy-efficient and pollution-reducing building technology. This technology uses straw for insulation within the walls of buildings. Schools and health clinics will be built with straw insulation by work crews trained by the project.

The environmental challenges Mongolia faces are acknowledged by the world community as both requiring a global and a national commitment. UNDP acts as conduit for a number of globally-supported programmes focused on local action. The axiom “think globally, act locally” is the principle guiding the UNDP/Mongolian Partnership for Progress’ environmental activities.

Note: Mongolia was experiencing ‘shock therapy’ during the 1990s, as well as austerity, in response to the collapse in subsidies and state supports when trade relationships with the Soviet Union ended.

Find in a library:

Worldcat.org: A partnership for progress : the United Nations Development Programme in Mongolia, UNDP Mongolia Communications Office, 1997

OCLC Number / Unique Identifier: 1248070177

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

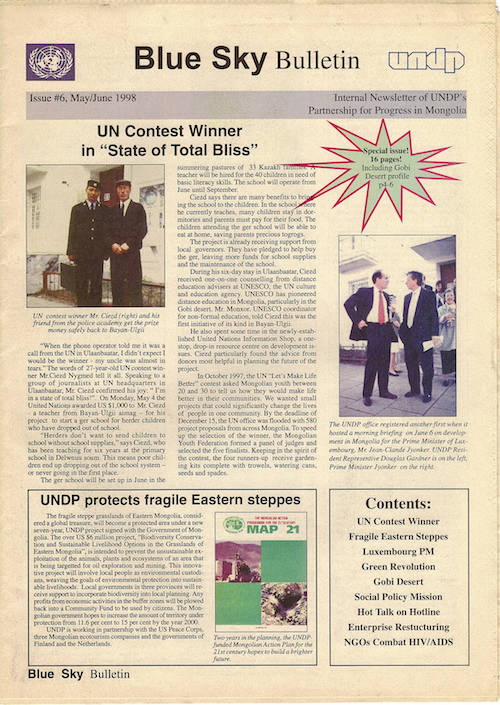

Publications produced by the Partnership for Progress (1997-1999):

Online media produced by the Partnership for Progress (1997-1999):

Works citing Partnership for Progress (1997-1999):

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5311-1052.

© David South Consulting 2021

You must be logged in to post a comment.